Author Ken Budd discusses international development's favourite dirty word.

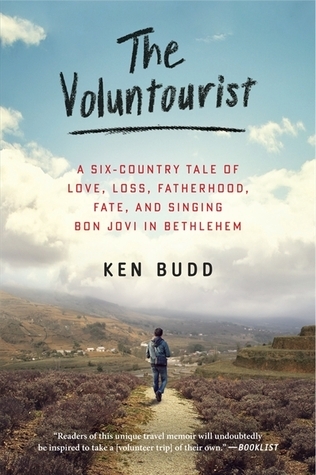

When writer and editor Ken Budd’s book came across my desk this spring, it wasn’t so much an exercise in “don’t judge a book by its cover” as it was in “don’t judge a book by its title.” I couldn’t help it—the title The Voluntourist: A six-country tale of love, loss, fatherhood, fate and singing Bon Jovi in Bethlehem left me feeling perplexed. While I do love a good Bon Jovi sing-along (who doesn’t, really?), I’ve been conditioned to be highly skeptical of anyone who actively refers to themselves as a “voluntourist.”

At Verge our mandate is “travel with purpose”—but it’s also travel with consideration for the environmental, economic, social and political impacts of the journeys that we’re taking across the globe. Language is a powerful tool and for me, “tourist” (in whatever form) has negative connotations.

But within 10 pages, I remembered why you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover—or by its title. Budd approached his volunteer projects (a whopping six of them—to New Orleans, Costa Rica, Kenya, Ecuador, Palestine and China) with honesty, humility, an ample dose of humor and just the right amount of skepticism.

In October, I caught up with Budd.

Verge: When I initially received a copy of the book, I have to admit that I was a little off-put by the title. “Voluntourist” has become a little bit of a dirty word.

Ken: Truth be told, I didn’t like the title. I was hoping for something grander, more sweeping. But everyone was like, “It has to be called The Voluntourist.” I’ve always felt that the word “tourist” is a bit misleading because I always felt like I was a worker more than anything else on these trips.

Before you wrote the book, were you aware of some of the negative connotations around “voluntourism?”

I think that’s reflected in the book. Everywhere I went, I thought, “Am I doing anything that really matters here? How much can you really do in two weeks?”

I understand the criticisms, but I came to see that there’d an intangible qualities to volunteer trips that a lot of the critics don’t take into account. The cultural interactions that happened were just as important—if not more important—than the work you’re doing. It changes the way we see people and it changes our perceptions.

I also felt there were a certain qualities to just being there and showing people that we were interested in what they were doing. When I was in China, working at a special needs school, that was a huge part of it. For these women, who work very difficult jobs, having me and a friend there was a big deal and it meant a lot of them that we were interested. They work difficult jobs and it kind of broke up the routine. After we left, they said, “We seem to laugh more when we have volunteers here.”

In the book you wrote about working in Costa Rica and that “in poorer parts of the world, parents are more likely to send their kids to school—instead of sending them to work—because American and European volunteers give a school cachet.”

I used to work for a volunteer-sending organization and with our volunteers, one of the things we always emphasized to them was that “by you organizing a workshop or information session, people are going to be more likely to attend, simply because you’re there.”

I thought that was fascinating—that just showing up can make a difference in a small way. And if it’s as small as someone sending your kid to school, that’s not small—that’s a big deal.

I felt that way in New Orleans, too. You get to New Orleans and you see the scale of what happened there and you’re holding your little paintbrush and thinking, “How can I make a difference?” But I was there nine months after Katrina. At that point, there still weren’t a lot of tourists coming back and I think it was important to people there just to have you there. And going home and telling people, “Here’s what’s going on in New Orleans.” That’s a big part of this. You take your experiences and bring them home and that ripple effect continues.

When you came home from these trips, were you cognizant of how the stories that you were telling people and the photos that you were showing people might reinforce or dispel stereotypes?

We all have stereotypes of people around the world and what we think is going on. If I told people I was going to Bethlehem, they would think, “baby Jesus” and be like, “Oh, that’s nice.” If I said I was going to Palestine, they would say, “Oh, you should wear a bulletproof vest. Are you going to be safe?” It was a completely different perception.

Anywhere you go, you find people are pretty much the same—we just want to have a good life.

At the end of the book, you include tips for making voluntourism trips happen. What questions should prospective volunteers be asking the organizations that they’re interested in volunteering with?

Are you creating partnerships? Or are you creating dependency? What’s the local impact?

As you know, a lot of criticism seems to come around programs with children. That was something that I worried about—with orphans, is my showing up and leaving two weeks later creating some sort of cycle of abandonment? In Kenya, I was assured that wasn’t the case, but I think it can be.

Any time you travel, you need to do your homework. But with these types of trips, the level of homework is increased because you’re interacting with people on a deeper level—which is part of the reason you do it—but that also increase the responsibility.

I think a lot of people go in thinking they’re going to change the world. It’s a two-week trip. Do what you’re asked, smile a lot, remember that you’re a guest and just don’t go in with huge expectations but realize there is a huge impact in small gestures.

Read Verge’s review of The Voluntourist: A six-country tale of love, loss, fatherhood, fate and singing Bon Jovi in Bethelem in the Fall 2012 issue, which is available online and on newsstands now.