Why getting all your shots won't protect you from the biggest travel health hazard abroad.

For most travellers and volunteers heading off to the tropics, their main health concern is usually infectious disease. Malaria and diarrhea top the list, while a myriad of infections ending in "iasis" (schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis, filariasis, myiasis, trypanosomiaisis and more) pull up the rear. While I am sure many of you will get diarrhea, and may well be told you have malaria at some point, with a bit of common sense, most of the others are unlikely.

In my opinion, and that of many other seasoned volunteers, it's all about the roads. Motor vehicle accidents are the greatest cause of death in travellers. Infections, on the other hand, account for less than 1 percent of mortalities abroad. If you are planning to travel to Nigeria, Peru or India (I could pick lots of different countries), the risk you face on the roads is even greater.

The reason for this state of affairs is not surprising—poverty—which is the main reason you would go away to volunteer there in the first place.

Firstly, think about the roads in many countries. Paving is often a luxury, and even when roads are paved, Jacuzzi-sized potholes are not unusual. Naturally, cars, trucks and buses zigzag back and forth to avoid these potholes—but unfortunately, they are often going in different directions. Roads are generally not well lit at night, and fluorescent white lines down the centre are non-existent. The shoulders of the roads, if there are any, might be populated by people with enormous loads on their own shoulders, or perhaps a wandering cow or baboon.

If you have ever travelled through the Andes, you might remember the numerous crosses along the roadside, each marking the spot where a bus toppled over a cliff. When I was there, traffic was allowed in one direction on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with the other days left for those headed the other way. Sundays were a free-for-all.

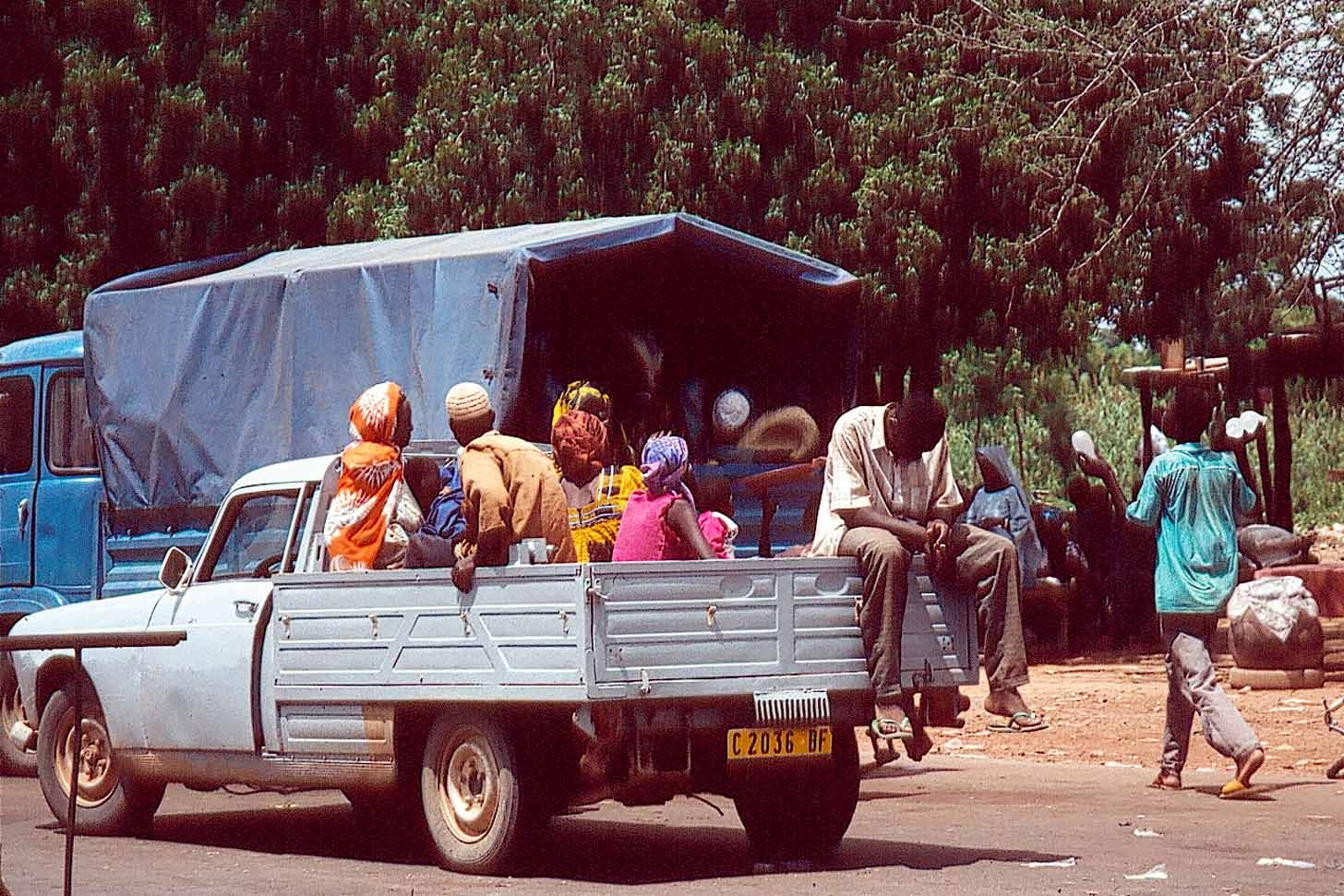

So much for the state of the roads. What about the vehicles? Well, let me be guilty of generalizing just a bit. Many public buses resemble 1961 Volkswagen vans. Cracked windshields are the norm, and sliding doors that just don't shut snugly are a way of life. I have one patient who travelled crammed against the doorway, and fell out of her moving vehicle. Another ended up paralyzed from the waist down after the open truck she was riding in ran into an overhead wire. Seatbelts, while you should hunt for them vigorously, are usually nowhere to be found. Dashboard dials usually don't work, though you can always count on music blaring during your trip.

If you think you're going to stretch out on your bus and get some rest while you travel, think again. Buses often don't depart on time. Rather, they depart when they are full. Really full! Local women and their babies seem to have the necessary skill to fall asleep. I have never been so lucky.

And lastly, the drivers. Again, I generalize, but rumour has it that the more people they carry, and the faster they reach their destination, the greater the payoff. Drunkenness, underage drivers and just plain reckless drivers are common. Sort of like over here.

So what is my advice? I am well aware that there is not always a great choice if you want to get from point A to point B in country C. But please consider the following:

• Avoid nighttime driving in rural areas (repeat this phrase every night)

• Avoid overcrowded buses (they are all overcrowded)

• Don't drink and drive, or get into vehicles with unsafe drivers

• Stay off of motorbikes, unless you are well trained and wearing a helmet

• Choose your taxi, and taxi driver, with care

• At least look for a seatbelt

• If you are travelling with small children, bring a proper car seat

• Use a local driver (in spite of my kind comments)

• Don't be afraid to tell your driver to slow down, and if he doesn't, get out

• Consider splurging on a bigger, more expensive (safer) bus

• Carry out-of-country medical insurance

My intention is not to scare you to death but, rather, to raise your level of awareness about the greatest risk you face travelling abroad. More about your bowels and the "iasises" in future articles.

Mark Wise is a family doctor in Toronto, specializing in travel and tropical medicine. He is the director of The Travel Clinic and acts as medical advisor to numerous NGOs and is on the board of Canadian Feed the Children. He has travelled to most of the places where you might consider volunteering.