Colin Wiseman goes to Ecuador looking for political enlightenment—but finds that teaching kids to paint may be as much as he can handle in one trip.

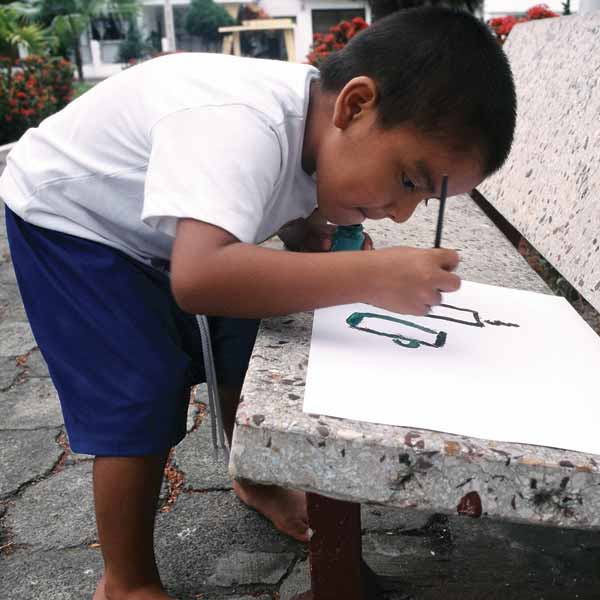

It was hot in the open air school house. Muggy and hot. In the corner, the third grade teacher dozed off with her cell phone cradled in her hands, sweat stains beginning to darken the armpits of her clean white shirt. Neatly uniformed children buzzed around me, their little hands tugging my limbs, screaming to one another in hurried Spanish. “What are they saying?” Uta, a Polish volunteer, demanded in her thick accent. Clutching a handful of paint brushes to her breast, she was trying to explain to the students—with me as the interpreter—that they needed to learn the colour wheel before they could begin painting. I had only been teaching art for ten minutes and already I was exhausted.

It was my first day volunteering at Escuala Sathya Sai, a small school serving grades one through five, just outside of the dilapidated resort community of Bahia de Caraquez on Ecuador’s central coast. Located in the shantytown referred to as Kilometro Ocho (kilometre eight), it derives its name from the fact that the one store in town was roughly eight kilometres away from Bahia proper. Escuela Sathya Sai is the work of a local philanthropist, Alfredo Harmsen, proprietor of the world’s first certified organic shrimp farm. It was not, to say the least, exactly what I had envisioned when I first pulled into Bahia on a hot and rainy May evening. In fact, I really hadn’t known what to expect. I had only found out where I would be working when I arrived the night before.

Lured to Ecuador by accounts of popular uprising and growing political consciousness in the lower classes, I was looking for a volunteer position that would allow me to get a first-hand taste of the class politics of Ecuador. After holing up in Quito for a week, I thought I’d found my opportunity when an email arrived from Rio Muchacho Organic Farm. “We know of a school on the coast that needs volunteers,” it read, providing an address in Bahia. “Just ask about Saiananda and they will tell you how to get there.” The next day I was on a bus to the coast, winding down through the subtropical mountains with little more than blind faith that I would find political enlightenment in Bahia. What I found was something quite different.

Political insignia can be found everywhere from the sidewalk to the tin rooftops of local homes in Bahia de Caraquez, but day-to-day life affords little time for political musings. Rather, most of Ecuador’s poor must perform hard labour for long hours to support their families. Because Escuela Sathya Sai is located in an area where most residents are poor—an estimated 86 percent of Ecuador’s rural population lives below the poverty line, according to according to Habitat for Humanity—the students at Escuela Sathya Sai deal with the hardships of poverty on a day-to-day basis. For instance, when not attending class one of my pupils could be seen selling the daily catch in the street while her father looked on behind a bottle of aguardiente (cheap cane liquor). He worked twelve-hour days riding the tide up and down the Rio Chone delta with a few shoddy fishnets. The luckier parents worked in the fields from sun up to sun down or raised chickens in a nearby factory. What was it that I could offer these people with only one month to give to their community?

What was it that I could offer these people with only one month to give to their community?My daily task of maintaining enough order in the classroom to allow the children to produce a drawing to hang on the wall seemed trivial in comparison to the hardships that the residents of Kilometro Ocho had to deal with every day: alcoholism, domestic violence and hunger. Despite my attempts to encourage artistic expression, or even just a few colourful scribbles, there was a handful of students in every class that preferred to hoard the crayons or ruin the work of their neighbour. When I asked a third grader, Fidel, why he did not want to paint any mountains (our theme for the day), he told me through tears that his paintings were ugly; crumpled balls of paper lay scattered around his desk. Instead of fighting for change, I found myself lamenting over my inability to touch the lives of the people of Kilometro Ocho.

By the third week of teaching I had found a rhythm in the classroom. Perhaps through repetition, or perhaps through continual encouragement despite the screaming, yelling and fighting, painting became fun. Posting the day’s work on the walls of the classroom brought a smile to everyone’s face, and when the less enthusiastic children found out that this would be rewarded with genuine interest, some of them started to enjoy art class.

Chaos became the exception rather than the norm, and, early one Friday morning, a second grader who had displayed an unwavering reluctance to put crayon to paper decided to paint a purple volcano full of hearts instead of breaking his paint brush and throwing it at his companion. Even if I wasn’t changing the lives of the students, at least I was able to offer them the chance to try their hands at painting with watercolours. During break, Katy, a bright and personable fourth grader, walked up to me and hugged my leg. “Uncle Colin,” she said in Spanish, “lift me up!” I complied, lifting her high into the air as she wriggled and laughed with glee. Children swarmed, this time with smiles on their faces, demanding, “Upame! Upame!” Lift me! Lift me!

As I watched Peter the English teacher wade through the swirling mass of children to join in the fun, I finally understood what my role was in Ecuador. Engaging with locals to produce political change was not a realistic goal for a month’s work in an impoverished neighbourhood. I giggled with the children, struggling to hoist them higher into the air. I did not have to find political enlightenment in order to help the people of Kilometro Ocho. Simply bringing a smile to the students’ faces was enough to make my work in Ecuador worthwhile.