Albert Koehl finds that, in Morocco, being a conspirator is sometimes part of the fun.

My co-conspirator glances back at me furtively as he turns the corner into a narrow alley. He is close enough that I can hear his sandals scraping against the ground but far enough ahead that our plot is unlikely to be detected by the Moroccan police. His faded yellow t-shirt lets me keep track of him despite his diminutive stature and the midday crowds in the medina of Fes-el-Bali. When we arrive at the famous Karaouyine Mosque, I approach him while pretending to study the façade of the mosque, and press the agreed-upon sum into his hand.

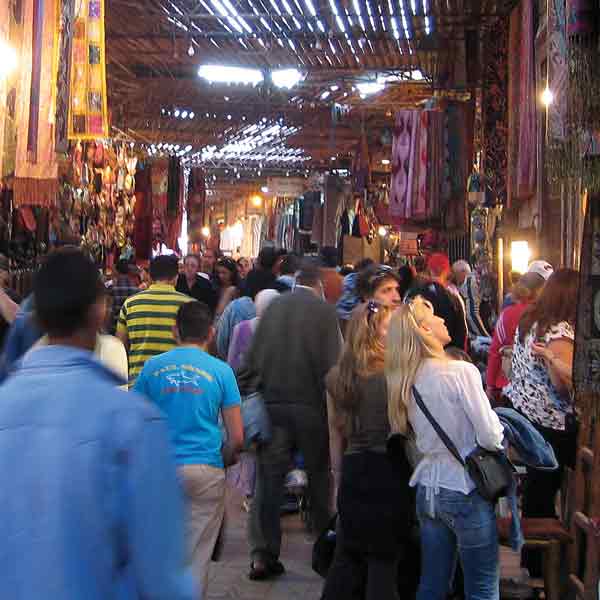

It never used to be so complicated to hire a guide in Morocco—not so long ago the challenge was to avoid them. When I visited Morocco 20 years ago, for instance, stepping off a long distance bus as a Westerner made you feel distinctly like a rock star. The attention from the gathered throng was at once intimidating and flattering. The would-be guides, who were of all ages, shared an impressive unwillingness to accept “no thank you” in response to offers to lead you to carpet shops, hotels, restaurants or other tourist sites. Well, times have changed and today the Moroccan government enforces, sometimes vigorously, a law that prohibits, under pain of imprisonment, unofficial or so-called “false” guides. This is part of a larger plan to attract ten million tourists annually by 2010.

After wandering for several hours through the maze of lanes and dead-end alleys of the old imperial city without coming to the famous mosque, I had decided to ask a shopkeeper for directions. His directions proved incomprehensible, so I suggested one of the kids in the adjacent square would be happy to earn some money to show me the way. At first I dismissed the shopkeeper’s reluctance to help, on the basis that he feared being caught by the police, as a ploy to extract a higher price. Moroccans love bargaining. But the shopkeeper’s concern seemed genuine and the plan was hatched to deliver me surreptitiously to the mosque for a fixed fee.

The fact that any local person, except state-authorized guides, is prohibited from accompanying tourists does make interaction with local people a bit problematic. The reputation of the Moroccan police and the country’s notorious jails means that local people would rather not leave any room for doubt about the motive for their association with a tourist. Fortunately, the hospitality and friendliness of average Moroccans makes it possible to overcome the law, with a bit of ingenuity.

Later that same day I peeked into a shop at the end of an alley to ask for more directions. (It’s a good conversation starter and allows you to choose instead of being chosen.) The ancient stone building with the simple wooden door turned out to be a workshop manufacturing ornamental metal light fixtures for export.

After chatting, drinking mint tea and getting a tour of the workshop’s interior—complete with electric machinery, vats of chemicals for the finishing process, and the rather suspect-looking wiring of its power supply—Abdul invited me to join him later in the day at a café in his neighbourhood in the newer part of the city where there would be no tourist police. He instructed me to follow him at a distance of about ten paces explaining that several acquaintances had recently been jailed on suspicion of acting as unofficial guides. I obeyed dutifully and followed him like some super-sized, stubble-faced member of a harem.

Abdul’s plan was that once we got out of the walled city he would hail a cab and jump in, while I would wait a few moments before joining him. Cabs are often shared in Morocco so there is nothing suspicious about a foreigner and a local person sharing a ride. Unfortunately, the driver started pulling away from the curb before the plan could be communicated, leaving me hanging onto the open door as the cab pulled away.

Instead of getting involved in a criminal conspiracy there is, of course, the option to hire a badge-bearing official guide. They are easy to find, and can be engaged for about 150 Dirham (DH) or $30 CDN for half a day. By comparison, a passable hotel room—depending on how you travel—can be had for under 50DH. If you are hoping, however, to avoid the well-trodden path of the tourist hordes then authorized guides may not be the best option.

Tourism is Morocco’s third biggest industry (after phosphate mining and remittances from nationals living abroad), which explains why the government is keen to pamper this source of revenue. Five million tourists visited the country last year, compared to about two million in 1985. Tourism brings in needed foreign currency while employing hundreds of thousands of people, although far less than the 40 percent of the population that depends on agriculture.

I obeyed dutifully, and followed him like some super-sized, stubble-faced member of a harem.

Developing tourism to boost the economy does have its downside. Some tourists expect back-home amenities, thereby encouraging the building of water-gulping golf courses while the country fights desertification. And government investment in tourism infrastructure is of little value if the visitors stop coming. Morocco’s tourism industry took a hit soon after the 9/11 attacks; a 2002 terrorist attack in Casablanca against tourist locales left dozens dead or injured and required quick action by Moroccan authorities to assuage the anxiety of foreigner visitors.

The reduced attention from unofficial guides is, on the whole, very pleasant—leaving aside the poverty that partly explains the problem. “Rock star” may no longer be a role the average tourist will play in Morocco, but there are still plenty of other roles offered by a country that is endowed with mountains, deserts, coasts, and exotic-looking cities and towns. But if criminal conspirator is the role that attracts you most, well, Morocco provides that option too.

Albert Koehl lives in Toronto.