Born into war in Lebanon, Doctors Without Borders veteran Richard Zereik knows what it means to be a refugee.

The central prison in Georgetown, Guyana, was much like one might imagine. High walls and filthy cells, an overcrowded courtyard, a shack in the corner for death row prisoners. Sweat, hustle and prison-house rules.

The young Canadian stood outside the rusted gates, fear and insecurity washing over him. He'd been to the prison twice before but always accompanied by colleagues or a local priest. This time he was alone.

“I just stood there. I thought of not going in but I knew if I didn't, they wouldn't take me seriously and I'd never get back in. On the other hand, I was thinking that if I did go in, I might get killed.”

The guards outside made sure that he knew that they thought he was crazy. “White boy, you ain't comin' out,” they laughed.

The young man went in, survived and helped launch the first drug abuse counselling program in the country's history. For the next several months he led group sessions inside the prison for inmates struggling with addiction.

Years later, Richard Zereik sits in a cafe in Montreal laughing about how his decision to enter the prison set the stage for a career that has taken him to many of the most violent, unpredictable and mind-bending places on Earth. For over a decade, the 41-year-old played a key role in medical humanitarian missions for Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), negotiating access, planning campaigns and finding resources for his colleagues throughout conflict, outbreak and crisis.

Born in to war in Lebanon, Zereik's family moved to Montreal when he was five. “My parents had two suitcases and the airline lost one of them,” he remembers. “They rebuilt their lives from scratch.”

The desire to travel and help the disadvantaged was always the plan, “I knew what it was like to be a refugee,” he explains. So in 2003, after finishing a psychology degree, Zereik cast his eye towards international development.

“I wasn't sure where to start so I did my research. Library books, magazines, even the Yellow Pages. I had no experience, no skills, so I just started writing letters.”

He happened upon Canadian Crossroads International, a group that sends volunteers on development exchanges around the world. “They were a good fit. They didn't really need me to have any skills and I liked the idea of a cultural exchange. They asked me where I wanted to go, I said wherever you think I fit, that's where I want to go.”

They suggested Guyana. He had done some disc jockey work and there was a project at a local radio station. It seemed perfect. He soon got his first lesson: most careers in development don't follow a straight path.

“The day before I was to leave I got a call from the group’s Canadian country liaison. She said good luck, hope you have a great mission. Oh, and by the way, I don't know who is picking you up at the airport, the [radio station] project fell through so I don't know what you're going to do there. I don't know where you're going to stay and the country representative isn't actually in the country. But good luck nonetheless.” With a day's notice and limited funds, he couldn't change his ticket so he continued as planned. Through a contact on the ground, he met a group that wanted to start a program helping addicts and soon found himself at the prison, learning on the fly.

After Guyana, Zereik returned to Canada, completed a Masters degree in Counselling Psychology and began to think of the next step.

“I had always dreamed of working for MSF,” he recalls. “When I was growing up in Montreal I had heard about their work in Beirut.” He attended an information session, was immediately hooked and applied. He told them that he was leaving on a trip to Europe but made it clear. “If you call me, I'll come back.” Weeks later, in Florence, Italy, he got an email. If he was near Rome, MSF wanted him to drop by the office.

“People started appearing out of nowhere, it was like they came out of the sand. In a few hours we treated hundreds of people.”

Recruiters, it turned out, had liked his work in Guyana. He had experience managing projects, people and money. Zereik, then 30, was hired as a field coordinator, responsible for managing missions, ensuring that the medical teams had the security and space to work. He was sent to Armenia, where long conflict with neighbouring Azerbaijan had left the country in crisis.

“Working in the region was a huge challenge. We were operating a long-term medical psychosocial program in a country with no social workers and with a culture that didn’t trust or care for psychology.”

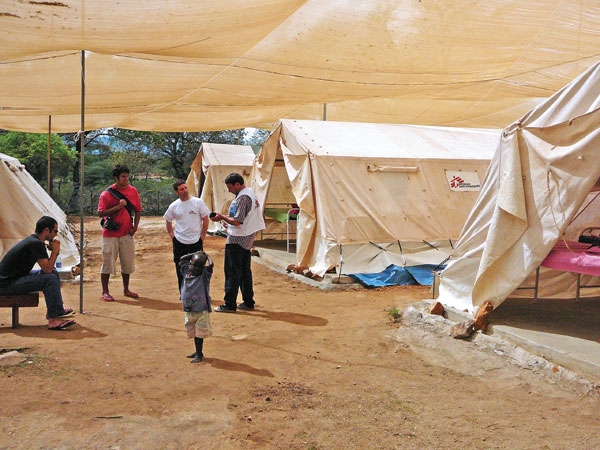

After a year on the ground, Zereik was offered a promotion. Feeling as though he wasn't ready, he opted for a parallel move to Sierra Leone, the West African country reeling from a bloody regional conflict. MSF ran seven camps for internally displaced people and three hospitals amidst the chaos. Over the next several years he alternated between MSF offices in Canada and return trips to the civil war in the Ivory Coast. In 2005, it was Darfur, where MSF had deployed a massive medical operation.

“Darfur is huge,” he explains. “All of it was a war zone.”

The violent conflict between North and South Sudan was notorious for its unpredictability. North Sudanese-backed Janjaweed mercenaries travelled on horseback or atop camels, often accompanied by aerial bombers, terrorizing rural villages across an area the size of France. MSF teams would get calls about attacks, assemble a mobile clinic and race—often over huge distances—to the scene. Part of Zereik's job was to ensure safe passage for the teams. “It was all about being able to read people, trusting your instincts and the people around you, your staff and the environment you were working in,” he explains. “There wasn’t much else you could do.”

There were no typical days. He remembers the day the village of Tama was attacked. A call came in and Zereik assembled a team and a mobile clinic—two trucks with drivers, medics, translators, the project coordinator and him. “We went in blind. It's how we had to work.”

As the team passed checkpoints, they felt as though they were intentionally being slowed down. Zereik, who speaks some Arabic, urgently tried to talk his way through. As they got closer, they were told people had fled Tama to a neighbouring village. So they changed course and, arriving in the town, put the word out that medics were there and could help.

“People started appearing out of nowhere, it was like they came out of the sand.” The team only had a short window of safety and had to act fast. “In a few hours we treated hundreds of people.”

In his line of work, the story repeats itself many times. Often flying blind, back at the prison gates. In 2006, Zereik worked with an MSF Operational Centre in Switzerland, part of a team managing the missions in Niger, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. He still made regular forays into the field. Again, nothing was simple. An outbreak of pulmonary plague in Northeastern DRC meant flying a team into a region in full crisis. UN peacekeepers had been recently kidnapped, rebel groups were everywhere and front lines moved quickly. As the plane approached, the pilot told Zereik that he had ten minutes to unload. Any longer would be too dangerous. Watching the plane fly away, he realized that he had no idea what was beyond the airstrip. “All right, let's go,” he remembers thinking. His team got to work and the outbreak was contained.

In late 2007, he lead a study to predict the challenges MSF teams would face working in an increasingly urbanized world. Again he was travelling the world, doing what he loved, but being away from his young family began to take its toll.

For the past few years, Zereik has worked with McGill University Student Services where he is currently an associate director of the program. The tug of the mission still grabs him, he admits, but he has found a peace in the quiet life and he can't really complain. “I still laugh sometimes in the morning when I turn on my faucet and there is cold water AND hot water. It puts everything in perspective.”