Helpful hints on how to cope when you find yourself unexpectedly standing in front of a class that doesn't speak your language, but wants to.

My family abounds with dedicated teachers, but for me, the prospect of exploring the world always triumphed over being trapped in a classroom with 30 children. So when I recently found myself before a horde of Venezuelan teenagers expecting an English lesson, I felt simultaneously panicked and nauseous.

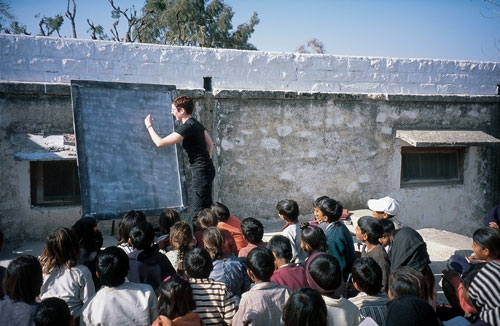

I stood with two other volunteers—Sarah from London and Marisa from San Francisco—like dissidents before a firing squad. None of us had any teaching experience, but schools in Santa Elena, in Venezuela's southeastern corner, long for English teachers, and our small volunteer organization requested we "take one for the team." With no training, and armed with only two small pieces of chalk, we faced the giggling children and began our introductions. Our attempts to correct their pronunciation only incited more laughter and a few typical catcalls from the back corner.

That night, we regrouped over rice and beans and reflected on that painfully awkward class. How could we, jack-of-all-trades volunteers who dabbled in tree-planting and very simple toy construction, enlighten a class when we could barely speak the students' language?

These days, English teachers are in demand at schools around the world. And with the changeable nature of volunteer work, a volunteer traveller might well find him or herself charged with teaching a class, sans experience or resources. How does one deal?

My fellow volunteers and I found a few successful tactics, largely by trial and error. For instance, inviting a local artist to make jewelry with the students, while we spoke about the craft in English, took the spotlight off us and provided some hands-on activity.

I found that requesting Spanish and Pemon translations for the English words I taught my students produced a less-intimidating language-sharing experience. We also learned that what the kids needed most was not bilingual translators, but simply a chance to listen to native English-speakers talk, since their past English instructors had little knowledge of pronunciation. That, we could handle.

Sandra Bit, from Edmonton, who has years of ESL teaching experience, offers a few more tips for volunteers charged with impromptu teaching assignments:

Be prepared, she says. With so many people wanting to learn the "international language of commerce" these days, all volunteers should add the country's education system to their pre-travel research. Find out what kind of English instruction, if any, local schools offer and what is expected of the teachers.

Use the Internet if you have access to it. Many organizations, including several universities, have ESL websites with printable resources and exercises.

Determine what kind of exposure your students have had to English. If they're familiar with certain TV shows or magazines, use that knowledge of "English culture" as a launching point for your lessons.

Draw on a talent, like playing an instrument or a sport, to entertain, involve, and break down barriers.

So even if you have no intention of teaching ESL abroad, preparing yourself for the possibility can only empower you as a traveller, and might ultimately make your volunteer experience even more memorable.