Stories of human trafficking survivors stir strong emotions. The desire to help is not a bad one; but the question is, how?

"We were so shocked to learn about the horrors of sex trafficking,” began the email from a well-meaning American church group, “and we’d like to come visit your project for a week to help unshackle women from brothels.”

I sat back in my office chair, confused—for one, because the anti-trafficking project I managed in rural Cambodia didn’t work in brothels. At all. And even if we did, I wondered why this group thought we’d allow strangers to leap into highly skilled and potentially dangerous work.

Their story isn’t unfamiliar. Human trafficking tends to stir strong emotions and impassioned desires for people to respond—which is a good thing, because it’s a crisis that cannot be addressed by a few. The fastest-growing criminal industry in the world, human trafficking enslaves anywhere between 21 million and 45.8 million men, women, and children around the world for the purpose of forced labour or commercial sexual activity.

With recent media attention and anti-slavery campaigns shedding light on an otherwise insidious issue, it’s natural that volunteers are eager to help. End Slavery Now currently lists over 500 anti-trafficking organizations with volunteer opportunities ranging anywhere between two-week commitments to more than a year.

Unfortunately, the capacity to care doesn’t translate to an ability to navigate the complexity of anti-trafficking work. This is especially the case when working directly with survivors emerging from exploitation. Yet, this is often the focal point for would-be volunteers. They want to meet survivors and hear their stories, lavish victims with gifts, walk through Red Light Districts, or participate in rescue operations.

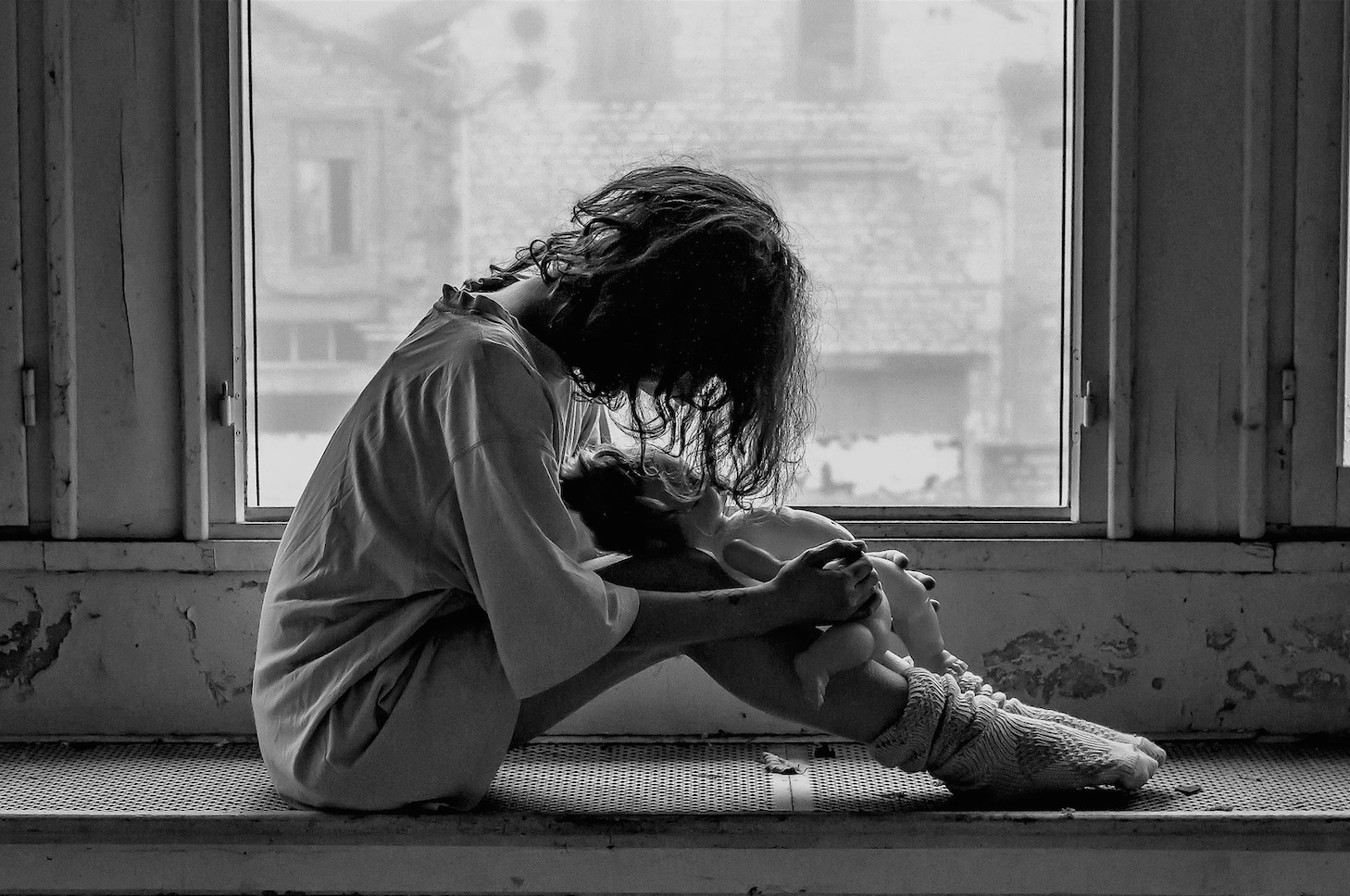

While some agencies do facilitate opportunities like these, many question their effectiveness. Survivors have endured intense trauma and abuse, sometimes by trusted family members or friends. Can a volunteer really provide the level of support survivors need, especially in the short-term?

Short-term commitment, long-term consequences?

For the past 12 years, NightLight Thailand has provided services such as life skills training, job opportunities, and emergency relief for women who wish to leave the sex trade in Bangkok. Its work has attracted considerable media attention, drawing the interest of volunteers—not all of whom are fully prepared.

“Anti-trafficking work is demanding and requires a long-term commitment,” explains Dan Turbiak, executive assistant at NightLight. “You have to be willing to be continuously in over your head. It is easy to get disillusioned, especially with expectations of success that are not reasonable in a limited time span.”

“The last thing we want is for our home to become a ‘museum,’ where visitors can learn about child trafficking, take pictures, and then head home."

Frustration and disappointment is only the tip of the iceberg. Volunteers may not have the coping mechanisms to appropriately handle the stories of abuse that survivors have lived. They're also not immune to the crippling experiences of secondary trauma, burnout, or compassion fatigue, which are real and common threats to service providers at any level of experience—even short-term volunteers.

There may be harmful consequences for the clients, too. After enduring years or even a lifetime of abusive relationships, survivors might be hesitant to trust and connect with others. The instability of volunteer turnover can, in turn, be distressing for survivors.

“It’s not fair to our residents—who are already emotionally vulnerable—to build trust and attachment to short-term volunteers, only to have them leave,” says Annie Schomaker, program director of the Illinois-based restoration home, Eden’s Glory, which serves women who have been trafficked in the United States. “It’s exhausting for survivors to step in and out of relationships with people who never return.”

The opposite is also true. A survivor may not bother to emotionally reciprocate if she or he knows a volunteer is only around for a week or two. That’s why Eden’s Glory asks volunteers to commit to at least one year and to be consistent in showing up for meetings, counselling appointments and outings with the residents.

Keturah DeChristopher coordinates the rehabilitative program CATCH Court, which provides tools for victims of trafficking in the U.S. to escape the cycle of abuse. She explains that building a rapport with these women requires time that short-term volunteers simply don’t have. Even if they do have the time, volunteers may lack the skills or the emotional maturity—which is not something that can be taught in a one-day pre-departure session.

“Professionals spend years learning and practicing trauma-informed care, personal boundaries, motivational interviewing, and more,” says DeChristopher, emphasizing the need for having a social work or counselling background, or at least extensive experience working with vulnerable groups. “Short-term volunteers are often not trained in these critical areas.”

As a result, volunteers may inadvertently cause harm by asking a survivor inappropriate questions, having destructive reactions to hearing his or her story, or offering poor counsel, which can be re-traumatizing.

“Going overseas to volunteer doesn’t mean you should have automatic access to people in vulnerable situations in the first place,” says Saskia Wishart, who has worked extensively with women in the Red Light District of Amsterdam. She notes how overseas volunteers sometimes assume roles they’d be in no way adequate to fill in their own country.

“The most you’re qualified to do overseas is what you’re most qualified to do in your own community,” Wishart states. “If you’re not already a teacher or a counselor or a social worker, why would you expect yourself to be a teacher or counselor or a social worker in a different country?”

Similar to the misgivings of “voluntourism” in orphanages, there is a growing concern that volunteers—unconsciously or otherwise—seek to interact with survivors to quench their own curiosity or to affirm their benevolence. Romanticized ideas of being a hero and sensationalized notions of what human trafficking looks like can cause real harm, misinforming approach and strategies. It can accidentally turn a human recovering from harrowing circumstances into a dehumanizing spectacle.

“The last thing we want is for our home to become a ‘museum,’ where visitors can learn about child trafficking, take pictures, and then head home,” explains Dave Clinton, the director of First Love in the Philippines, which provides housing and care for girls who have survived sexual abuse. “Groups of visitors can be detrimental and distracting to the ongoing work of healing and restoration.”

How can I help?

There is space for volunteers in the anti-trafficking field if they’ve been properly screened, trained, and monitored—it just might not be in the capacity of working one-on-one with survivors.

“We don't let just anyone into our aftercare home, but we do find value in letting good people with special skills in,” says Clinton.

Specialized skills might include trauma counselling, case management, and facilitating job or life skills training. Other competencies that benefit organizations, but happen behind-the-scenes, include grant writing, graphic design, construction, marketing or communications.

Additionally, an organization may not have an explicit focus on anti-trafficking but can still help create the socio-economic conditions for people to be more resilient against exploitation. For example, Cuso International, VSO, Crossroads International and Uniterra all offer short and long-term volunteer opportunities that empower women or create livelihood opportunities which, in turn, help reduce vulnerability to exploitation.

In either case, the best way a person can approach volunteering in this capacity is by reaching out to reputable anti-trafficking organizations and asking them what their needs are. Often, those needs are neither high-level nor particularly thrilling. It might mean washing dishes, cleaning offices, or organizing supplies to free up the time of trained professionals who can then focus on their job.

“It isn’t glamorous to come home and tell your friends that you scrubbed toilets for a week,” says Schomaker. “But if we want to volunteer overseas, we have to ask organizations what their needs are and be willing to do the dirty work without the glory. And that’s when you know you’re in it for the right reasons.”

Other Ways to Help Survivors of Human Trafficking

The fight against human trafficking is about more than working directly to rescue or rehabilitate survivors. It’s also about generating awareness, lobbying for better legislation, and supporting trained professionals who work on the front lines. Here are a few other alternatives:

Educate yourself.

Look beyond documentaries that offer a narrow narrative and instead seek out multiple reliable sources to gain greater understanding. Learn how to identify and report suspicious or exploitative activities in your own area to law enforcement or your national human trafficking hotline number (in Canada, the number is 1-855-850-4640; in the U.S. it’s 1-888-3737-888).

Invest in your community.

You don’t have to volunteer specifically with an anti-trafficking organization in order to fight human trafficking. Volunteering with local agencies that support people in vulnerable situations—such as people who are homeless, in poverty, reintegrating from prison or in foster care—can serve the same purpose.

Make informed purchasing decisions.

Supporting fair-trade or ethical companies that refuse to use slave labour is one of the best ways you can fight human trafficking in your daily life. Some companies, like Camano Island Coffee, go even further and give a percentage of their profits to anti-trafficking work.

Buy products made by survivors.

When you buy from social enterprises, such as jewellery from NightLight, home goods and fashion items from To The Market, body care products from Thistle Farms, or scarves from Eden’s Glory, you’re contributing to the recovery of survivors.

Give or fundraise.

One of the greatest struggles of non-profits is the lack, or instability, of funding. Instead of spending money to volunteer abroad, consider allocating those funds to help an organization hire a local trauma counsellor (or whatever their needs may be). You can give to any of the non-profits mentioned in this article, or others such as Freedom United, World Hope, Chab Dai and the Set Free Movement.

This article originally appeared in Verge's Spring 2017 issue.