A youth project on the island of Zanzibar has young women in the community taking pictures. But what they are taking away from the project is infinitely more valuable.

In a simple, four-room community centre on the outskirts of Stone Town—located on the Island of Zanzibar off the coast of Tanzania—Kate Spence hands four young local women disposable cameras for the first time in their lives. And, strangely, none of them seem remotely interested.

For 26-year-old Spence, this doesn't seem like a particularly good start to the Gender In-Focus initiative, a newly launched programme delivered by Canadian non-profit Youth Challenge International (YCI). The initiative provides young Tanzanian women with basic photography training and disposable cameras in an effort to generate discussion and ultimately, build a support network among women in the community. But the apparent lack of interest on the part of the young women wasn't the reaction that Spence had anticipated. "I had been so excited about this project," recounts Spence, "and at that moment, I thought it wasn't going to work."

So Spence turned to the translator who had been helping her, and asked her to reiterate that it was the women themselves who would be taking pictures—and then everything changed. "Their entire body language changed and they became animated and excited." says Spence. "None of them had used a camera before and they were so curious as to how they worked." At the next meeting, five more women were in attendance, and by the following week Spence had distributed cameras to 16 women.

The Gender In-Focus programme is unique in Zanzibar, where women typically don't have much opportunity to get involved in public life outside the home, according to Spence. While women may work outside the home, they still tend to be mainly responsible for chores inside the home like childcare, cooking and cleaning.

The goal of the programme is to use the women's own photographs as a springboard for discussion about issues that are relevant to them, like reproductive health, family and childcare. As importantly, the discussions provide an opportunity for women to gain confidence in expressing themselves in a supportive environment, and build a support network among themselves. The concept is simple: the women receive basic photography training from Spence and other volunteers. They are then encouraged to take pictures of women in the community—specifically about daily life for women in Zanzibar, and also the strong women in their lives. After taking pictures, the they come back together to discuss the photos and what they mean to the women who took them. Besides giving the women the chance to express themselves creatively, the discussions are also meant to identify and address issues that come up as a result of their photographs.

Photo-therapy has become something of a buzzword lately, made famous by the documentary film, Born into Brothels, which follows a New York based photographer to India, where she teaches several children in the red light district of Calcutta to use cameras. Simply put, photo-therapy uses a person's own photographs to generate discussion about what's on his or her mind. Recently—as in the case of the women in Zanzibar—the technique has been used as a way of generating discussion about issues that are important to participants, in an environment where they feel comfortable to speak freely.

The idea for a photography programme had been in the works before Spence decided to volunteer in Tanzania. Deanna Duplessis, 25, from Peterborough, Ontario, had been working with YCI in Zanzibar to establish the first ever women's club through ZANGOC—an umbrella organization for 29 NGOs doing HIV/AIDS work on the Zanzibar Islands. Duplessis says the young women tended to be very shy and reluctant to participate in programmes and events at the centre. After talking with local women and other volunteers who had a strong interest in photography, they thought a photography project might be an ideal way to get the women involved.

Before Spence left Vancouver to join the project, she was able to raise enough money purchase 22 disposable cameras. This, along with funds raised by fellow volunteer Maia Rotman, was crucial in getting the Gender In-Focus programme on its feet.

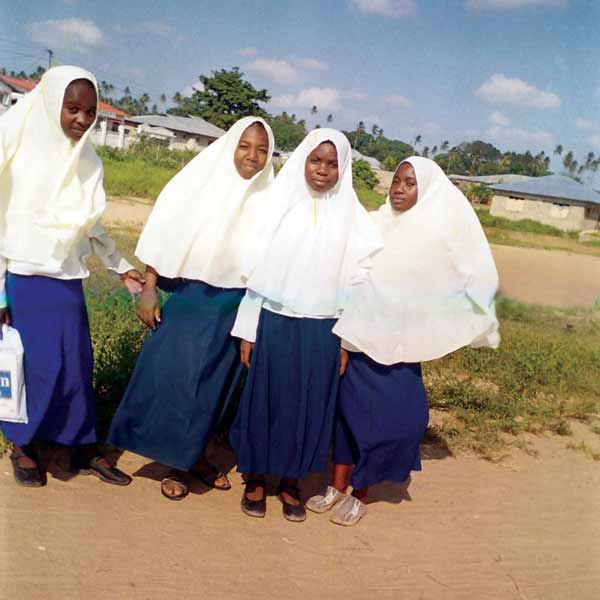

The photographs taken by the women portray everyday life for women in Zanzibar: a woman working in her garden, children playing, a woman doing chores in front of her home. When the women come back together as a group to discuss the photographs, the volunteers encourage them to explore what the pictures might reveal about the strength and role of women in the community.

Volunteer Pam Bruce is convinced that these discussions helped the women gain confidence and start thinking outside the box. Soon after completing the programme, one woman worked as a co-DJ at a community event—a clear break from local gender stereotypes—and in a second case, a group of women stood up and demanded their fair share of time on the basketball court. Small strides, but according to Bruce, "they are just more open and communicative as a result."

At the close of the programme, the participants chose images that they were proud of, and these were enlarged and exhibited along with the stories behind them. The response to the programme has been tremendous: the exhibition has now been viewed by more than 400 community members at various community events. It was showcased at the Zanzibar International Film Festival and has been shown throughout Southern Africa.

Bruce says that the responses by individual viewers at the exhibition have varied. The biggest detractors were local men. Bruce says that in a traditional society like Zanzibar, the lives of women and children are usually kept behind closed doors. She speculates: "Maybe it's a little too personal and they didn't feel comfortable having them displayed." There has been some jealousy from local young men, since the focus of the programme is to showcase women's work. In order to address this, YCI and ZANGOC are looking into ways of involving young men in future programmes. Bruce thinks the reason that the programme is so effective in getting women to open up, is the fact that the group can use the photographs as a starting point for discussion, and perhaps even more importantly, the discussion is driven by the participants themselves—through their photographs. Comparing this programme to other types of discussion groups, Bruce says, "Discussion groups are often geared towards the workers [discussion leaders], and they [the participants] may not feel comfortable enough to bring up issues themselves. This is a unique way to get them to start talking."

While an immediate aim of the Gender in Focus programme is to improve the women's confidence within their photography group, Duplessis hopes that this will extend into other facets of their lives as well, like the fight against HIV/AIDS. She points to the fact that in many cases, women do not have the option of refusing sex or demanding safe sex. In addition, fear of testing and the stigma that's attached to it can be a big deterrent to getting tested and, ultimately, to obtaining treatment. For a woman in Zanzibar, just the simple act of getting tested—regardless of the result—can earn her a reputation in the community as being promiscuous or being a prostitute. Duplessis says that education and empowerment are key to making women less vulnerable to the threat of HIV/AIDS.

And the programme indeed seems to have had an effect on the women's outlook on HIV/AIDS. In March 2007, following the initial photography project, about ten women from the group had themselves tested for HIV—most of them for the first time. One of the participants said she was getting tested because, "I had the courage and my friends to support me."

Some of the main challenges to the programme are logistic: cameras are pricey, and the programme's budget is modest. Preserving the prints and negatives is tricky in the harsh environment of Zanzibar, where they can be damaged by sun, heat or rain. Duplessis hopes that a programme where men and women are both involved might overcome the jealousy currently felt by the men. Ultimately, though, Duplessis acknowledges that development work involves a certain amount of trial and error. "One of the first things you learn working in the field is that the secret to success is to stop expecting it to look the way you thought it would," she says. "Development is a field that is very well versed in what doesn't work, and not very well versed in what does. We have been learning as we develop this project, and each phase of the programme gets a little bit stronger."

"One of the first things you learn working in the field is that the secret to success is to stop expecting it to look the way you thought it would."

Duplessis says that, based on the success of the programme, YCI plans to continue their photography programme in Zanzibar with support through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) Global Youth Leadership Program. Along with Spence—now a programme assistant on a CIDA internship—and Bruce, Duplessis is raising money to expand the project, and maybe even include a component in Canada. Pamela Bruce, currently a teacher-in-training at the University of Toronto, has already displayed the photographs in Toronto-area schools in an effort to foster cross-cultural understanding. She has also started her students and the Zanzibari women writing to each other about the photographs and life in Tanzania.

Both Spence and Duplessis will finish their contracts in Tanzania in 2008. But the experience has prompted them to look at similar fields upon their return to Canada—Spence in counselling; Duplessis in the field of global public health. Both look at their experiences in Tanzania—and with the In Focus programme—as invaluable.

Until they return to Canada sometime next year, Spence and the volunteers continue to live in Stone Town. They have no hot water and buy their electricity using prepaid cards. They take crowded mini-buses, called dala dalas, to work everyday to the community centre. But according to them, all this is just part of the fun. "You never know what each day will bring," says Duplessis. "It can be frustrating, challenging, chaotic, and exhausting at times. Overall though, I absolutely love the chaos, the constant challenges, the obstacles. That's all part of the process after all."

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).