An international education is fundamental to promoting a world that actually gets along.

Dr. David Fenner thinks that an international education is fundamental to promoting a world that actually gets along instead of blowing itself up.

For the next five minutes, think of all the reasons why you would never study abroad. Didn't know it was an option? Can't afford it? Marks aren't good enough? Don't know where to look for information? That's it—keep talking yourself out of it.

Now, think about those reasons. Are any of them insurmountable? Unlikely, right?

Now try to talk yourself into it—what's in it for you? How about learning a new language, or giving yourself a change of scenery, or enhancing your resume, or broadening your perspective? Still not convinced?

How about this: a little thing like saving the planet.

If you're just coming around to the idea that it might be fun to live in Florence and learn Italian, that may sound a little over the top. But Dr. David Fenner thinks that an international education is fundamental to promoting a world that actually gets along instead of blowing itself up.

Dr. Fenner, Assistant Vice Provost and Director of International Programs and Exchanges at the University of Washington, says that in his opinion, one of the biggest failings of many universities (he confines his comments to American universities, but feel free to extrapolate), is an unsettling silence about war, and particularly our role in it.

"I'm trying to make the point," says Fenner, in a telephone interview from his office in Seattle, "that we're not neutral on things that involve death and destruction and cluster bombs. We've got to be advocates for a kind of education that will actually educate a group of people that leads us forward rather than just accepts the status quo."

He says that international education is important in getting people thinking about the world outside their own backyards. "For a start, it gets people out of their comfort zone."

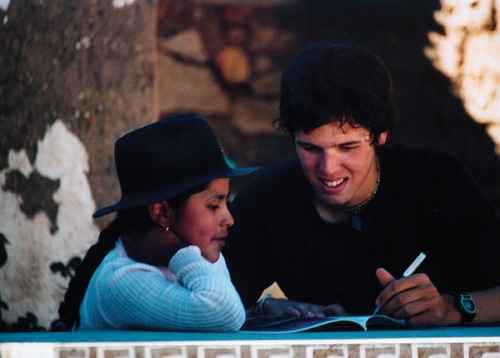

"It starts with putting a human face on people from Ghana, or even in Paris or Tokyo. They stop being 'them' and start being Ikira or Jean-Claude."

Fenner recalls his own experience as a student, many years ago, studying abroad for the first time in what was then Yugoslavia. He says that he's never stopped thinking about the people there as 'we' rather than 'them'.

"When you live somewhere for a few years, suddenly it's not bringing to mind just stereotypes. It's a place with a culture, a history, politics, a complexity, a human face, that you wouldn't have had if you'd just stayed in your own little cocoon.

"When I watched the Serbs raining mortar shells down on Bosnian soccer pitches, I wasn't asking myself 'How can they do this?'

"I was asking myself, 'How can we do this?'"

"Students coming from a year abroad aren't going to be a passive, neutered presence in the classroom. They're going to have a whole lot to contribute."

That difference in perception, the leap from the idea of a faceless, anonymous 'other', is one of the first things that breaks down in foreign study, he says. And it's a crucial first step. A person who has spent time studying in another country and has made that leap is going to be a completely different student once he returns to class in his home institution. Fenner thinks the spin-off effects of having students like that in the classroom are enormous.

"Students coming from a year at a Japanese university aren't going to be a passive, neutered presence in the classroom. They're going to have a whole lot to contribute to a discussion about east-west issues, trans-Pacific issues, all kinds of issues. They're going to start demanding more and more of the faculty - that they too become more globally engaged in a way that maybe twenty years ago, at least at this university, they didn't feel from any quarter."

Asked if he thinks that universities have ceased to be the hotbeds of dissent and activism they were in the 60s and 70s, Fenner says that he thinks that many educators have retreated from being as vocal as they should be about war. "That doesn't mean introducing a partisan agenda, 'conservatives think war is ok and liberals don't,'" he says. "War is not ok."

But, despite his misgivings about what he sees as complacency within universities, Fenner is optimistic. He says that he's starting to see a rebirth of student activism. He's convinced that it will be an important force in getting universities to re-evaluate their role in speaking out against war.

What is needed, he asserts. is a generation of truly educated young people around the world who reject the use of war by any nation. As an international educator, he says that one of the best things he can do is to make education 'three-dimensional' by making it immediate, personal and global.

"We have an obligation to the planet and to each other, to figure out how to agree and disagree, but without violence. You don't blow people up because you disagree with them."