High in the mountains of central Bosnia and Herzegovina, the village of Lukomir perches between a cliff and the empty valley of Pogled. In summer, shadows of clouds drift across shaggy mounds of hay and yellow flowers burst beneath tumbled stone walls. The lone road to Lukomir cuts through it all, brown and bare.

For Lukomir to resemble the "unspoiled" myth, it must remain poor.

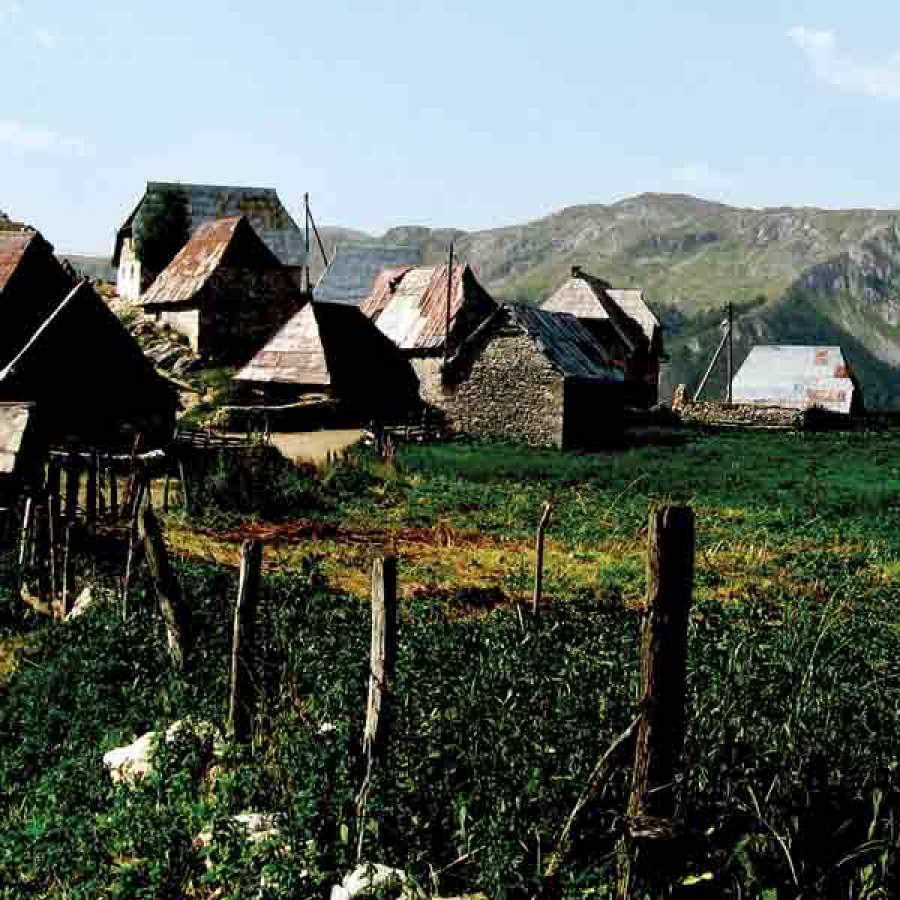

Every step closer to Lukomir is like stepping back a decade in time. When I arrive in 2007 it could be 1307 if not for the tangle of power lines. The mud streets are packed with fallen wool and the air is thick with the scent of manure. The old stone houses squat on the ground, pounded down over the years by snow and wind. In the shade of a mud wall an old man leans on his curved shepherd's cane.

Here, in the highest and most isolated village in the country, residents from semi-nomadic stock still herd sheep and use their wool for everyday clothing. The road was built after World War II, but was impassable nine months of the year with winter snow and spring mud. Even in summer only all-terrain trucks could reach the village, after hours of lurching.

Lukomir's location spared it destruction during Yugoslavia's disintegration in the wars of the 1990s. Only the small school was destroyed by shelling and no one was injured.

International funding flowed after the war and in 2004 the road was improved, allowing ordinary vehicles to access the village from about May through November. Upon the road tourists come and, going the opposite way, the residents of Lukomir leave for better prospects in Sarajevo and beyond. The population is estimated at around 60 in the summer, less than a third of that in winter, and declines by a family or so every year.

The road has made it easier to transport the herds to lowland villages for winter, yet many older residents stay in Lukomir, awaiting the summer return of their children and grandchildren who will help them to pasture the sheep, and to make a little money from tourism.

"What we're trying to do," explains Thierry Jubert, co-founder of the Bosnian eco-adventure company, Green Visions, "is to allow people to stay in the village in a sustainable way and to give opportunities back to young people to be involved in summer tourism... and trying to get houses restored."

Green Visions has expanded their capacity since the road improvement, bringing up to 30 people a month in summer. Other touring companies bring a few more, and some visitors arrive in their own vehicles or, like me, on foot.

As I stroll through the village, women in traditional Bosnian Muslim dress poke their heads out the windows and ask me if I want to buy their hand-woven socks. Some come to me and show me their wares, complex geometric weavings of line and colour. When they see I'm uninterested, they walk on.

I begin bargaining with some villagers for a place to stay overnight. A man pulls out a wad of Konvertible Marka while his mother and grandmother squat on the stones beside him and watch me. Another woman comes by and starts arguing with the man, then turns to me and tells me I should buy her socks instead. The old women cackle and raise their bloated arms at the competitor and she leaves.

Eventually I find the woman who has keys to the new guest refuge, a vast space with at least twenty bunks—all empty. The refuge sits on the grounds of the bombed school which was never rebuilt or replaced.

The woman motions me to come into her house and I take off my shoes and bend to enter, feeling the cool earthen floor on my feet. I sit down on a rough-hewn bench and the woman brings me a tray of spinach burek, long coils of thin sour dough.

The old man with the curved cane emerges from the light of the open door. He pulls a book from a shelf and shows me the collection of his grandchildrens' drawings of people, dogs, houses and creatures I can't place. Using hand gestures I ask him where the children have gone. He shrugs, as if the answer is obvious.

"Sarajevo," he says, making the motion of a steering wheel with his hands, clenching them slowly in the dark air.

Among the children that remain in the village, there is a girl named Adilisa who speaks a little English. She takes me to her house, where an old woman sits beside the chickens, spinning and separating wool with the salvia from her mouth. She runs the rough strings of raw wool through her lips, and with a bright red paddle in her other hand she pulls the strings straight and wet and coils them neatly in a spiral. I buy socks from her.

Maybe Lukomir is fated to become a museum village, shrinking year after year. USAID has fronted millions to advertise Bosnia and Herzegovina as a tourist destination, branding it as remote and undiscovered. For Lukomir to resemble the "unspoiled" myth, it must remain poor. Should tourists demand that it stay poor to meet the expectations of those of us who lost such places of our own long ago? And, can Lukomir weather the tourist gaze without becoming alienated from itself?

To read more about Lukomir, check out the web exclusive article The Trail to Lukomir.