When I first boarded my plane to South America over a year ago, I had to confront the truth I had been avoiding—my Spanish was dreadful. Sitting down next to a Bolivian lady who would be my companion for the next 10 hours, I realized that my faith in my linguistic abilities had been misplaced. I had studied religiously for my final month in the UK, but it suddenly felt like those studious hours had been in vain.

As a native English speaker, I am used to relying on my mother tongue when I visit other countries. But this has always felt like a fault plaguing my ability to travel.

For many people this may seem strange, as the vast majority of visitors and tourist industries in most countries use English as their go-to language of communication. A quick Internet search will bring up countless articles articulating the necessity of learning English for those wishing to travel.

As a native English speaker, I am used to relying on my mother tongue when I visit other countries. But this has always plagued my ability to travel.

But what about us monoglots? Yes, it’s a great advantage to be inbuilt with the capacity for communicating with the vast majority of people you may encounter when you travel. But what about all of those other interesting people with whom you are unable to speak, due to a lack of familiarity with the local language and what feels like a miserable ability to learn another?

So when I arrived in Bolivia, I was determined to put everything into my learning of that elusive second language.

A year later, and my current volunteering position in Peru with the Latin Foundation for the Future (LAFF) is almost entirely dependent upon my inexact wrestling with Spanish. But each day I am reminded by how far I have come from that initial encounter on the plane from Madrid. It has been a slow process, but one from which each day it feels like I am emerging a little more victorious.

This week I delivered one of my most interesting workshops to date to the young people of the Sacred Valley Project in Calca, 10 minutes by colectivo from the tourist hub of Pisac. Having been kindly donated six cameras by Alianza Andina, who also work in the local area, LAFF had decided to use the cameras for a photography project to help the girls proudly showcase their identities and communities. Coming from tiny, distant villages, these girls live in the house in Calca during the week to attend school, and we wanted to encourage them to present their rural roots. Added to this, the photographs would serve as a window into one another’s lives, given that few had ever visited each other’s communities.

Before each workshop that I deliver, my teaching instincts kick in. What I’ve known ever since I started teaching is that regardless of the context, planning is the key. If you want your class to run smoothly—for your participants to leave smiling and genuinely having enjoyed the past hour— then you need to plan. Few of us are gifted with the ability to wrap our listeners around our verbal little fingers without some idea as to how this might be achieved.

Delivering workshops in another language—and one in which, I will readily admit, I am still far from perfect—requires a whole new level of planning. I write questions in Spanish in case I suffer a brain freeze when attempting to explain a topic, and make constant notes on the side of my plan to make sure the vocabulary I need is at the tip of my tongue. But my most useful aid for the workshop had to be our local volunteer Ivan, ready to jump in with only a moment’s notice when I inevitably start speaking rubbish.

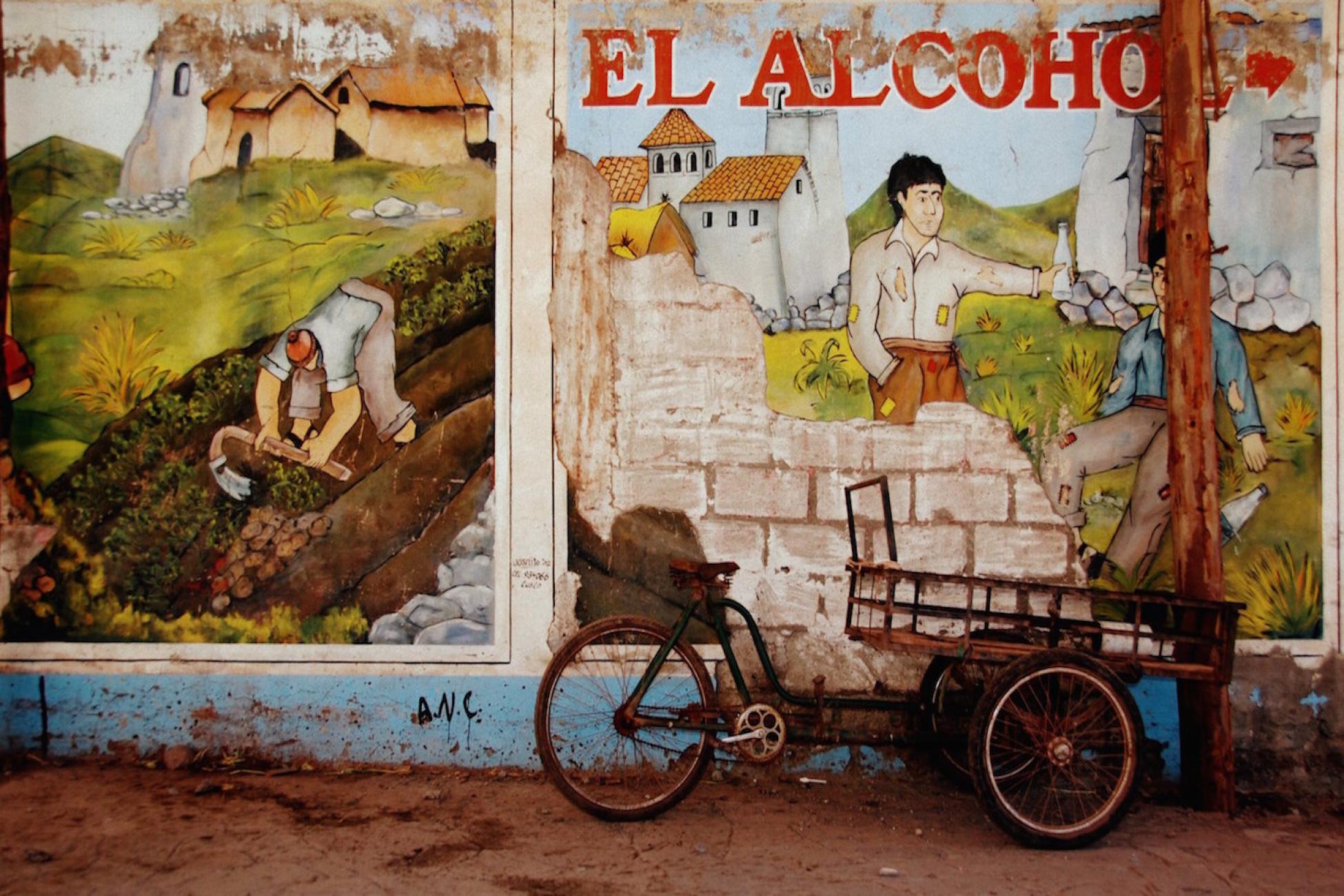

But despite this overload of planning, what I saw when we began the session was that one of the reasons that photography is so powerful is that it requires so few words. The 15 images that I had picked from internet searches to offer different perspectives and photographic techniques were the “words.” They were our way of communicating, regardless of the languages we spoke.

I was again struck by the similarities that you find, whatever the context. This time it was by the girls themselves. When asked to select and explain a photograph with which they most identified, for many, the images—most probably shot in Europe—released memories of their “pueblos,” their home villages in the soft setting of the sun over pastureland, or the ribbon of colour smeared across the sky from a distant rainbow. It made me realize that sometimes we place so much emphasis on words that we forget that images and what we can see before us are sometimes a more powerful form of communication. They’re an image that we can share and identify with, regardless of who we are, or where we come from. It is for this reason that I genuinely believe this project will be so powerful for these young girls in the Sacred Valley.

For me, learning Spanish has opened up this opportunity into the lives of these young girls. Over the coming weeks and months, as they go back to their communities and begin the slow and personal process of documenting their lives, I will be a spectator—but a welcome one.

Working with LAFF, and the other organizations with whom I volunteered in Bolivia, has helped me learn enough of the language to communicate. It has also opened doors to communication—with people and in places that might be a mere stop on the colectivo for other tourists, but where life is different, rawer and surprisingly open to accept you.

Ultimately, this workshop proved that no matter whether your grasp of your second, third or whatever number of languages is perfect, there are ways of communicating, which are sometimes more powerful than words can ever be.