After all, I stand out enough as it is as a white person—I do not want to come across as an arrogant or righteous white person.

I constantly wonder how any major decision I make at any given moment here in Nicaragua will negatively or positively affect those around me. I ask myself “will I be stepping on toes?” or “when is time to put aside my identity as a foreigner and look at a situation for what it is.” I had this dilemma last week when my mother came to visit me here in Nicaragua. She could not sleep due to what we both quickly realized was causing some nasal congestion and headaches, my neighbour’s yard.

The woman who lives next door is a character straight out of a book. Her dog and pig are cooped up in what looks like the pit of hell and are joined by a large cage of three or four crowing cock-fighting roosters. This scene goes on while she constantly stews, churning out pork dishes from dawn until dusk. Her specialty: cooking a traditional Nicaraguan delicacy called “nacatamal,” a rich fermented corn and pork dish wrapped in plantain leaves. It is a dish that makes many a Nicaraguan’s mouth water just at the mention of it. It is the bustling little business of selling this rich dish out of her home, however, that is literally smoking me out.

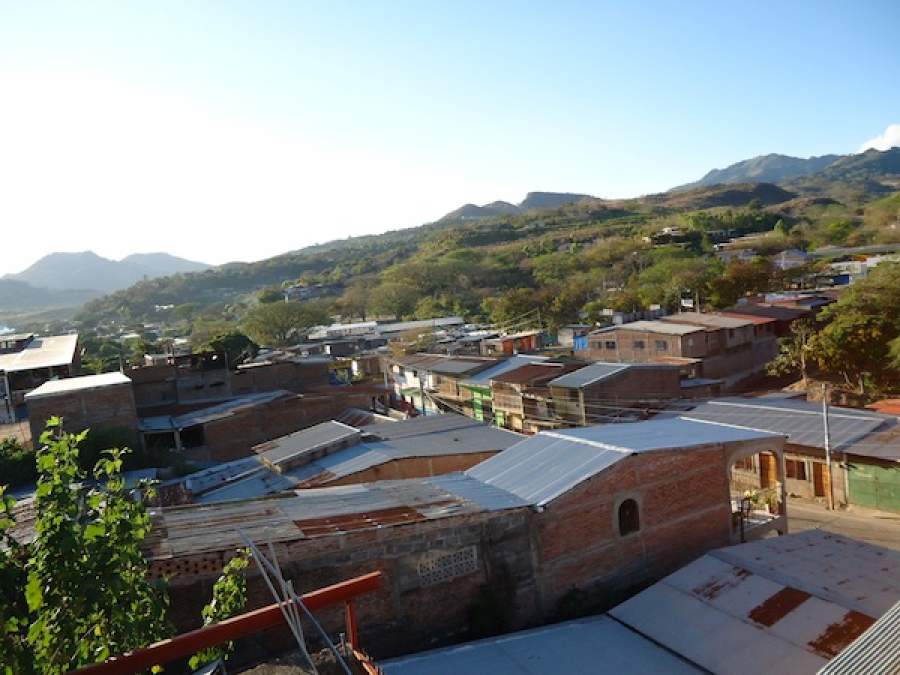

I have become accustomed to many things here in Nicaragua. Take the noise, for example. I arrived to the country frustrated at the fact that I was wakened up every morning by the roosters crowing and the sound of bustling traffic at 6 a.m. I now, however, name the so-called noise pollution a “symphony” of sounds; car horns, roosters, dogs barking, horses clopping, not to mention the advertising-obituary announcement truck, combing the streets daily and nightly, just to name a few. I have also become accustomed to the smoke that barrels into my apartment all morning and all night from the neighbour’s narrow outdoor kitchen, which consists of two concrete walls and a tin roof. It wasn’t until my mother woke up almost suffocating at 4 a.m. every morning that I noticed my own congestion and we connected it to the problem.

My mother and I had many good conversations, some in frustration. “How is it that she is still producing smoke at 9 p.m.?” we would ask each other. Or, “Isn’t she affected by the smoke?” I had always pondered these questions but when my mother arrived, she suggested I seriously consider taking action to stop the problem. The foreigner part of me, afraid of stepping on toes and aware that this was someone’s livelihood, decided I would just put up with it and even when my mom was visiting, I didn’t notice the smoke as much as she did.

From an individual’s point of view whose health is suffering, however, I have decided to take on another stance. I have come to the conclusion that no one needs to suffer from health problems, whether foreign or local. Everyone has a right to breathe clean air and everyone has the power to stand up for this right. I spoke with my director and it turns out she has already faced difficulties with my neighbour before. It turns out she has brought her customs from the countryside and tried to adapt them to city living, including having a pig in her house, right beside the kitchen. This is prohibited in Matagalpa according to my boss.

The next step will be to head to the Ministry of Health and Sanitation to enter a complaint. It is not my intention to destroy a livelihood, but to help this women do what she does without affecting the environment and the health of those around her.