It seemed like an archaic tradition; one that favoured a family’s social connections, property and status over individual happiness. Plainly put, I couldn’t see why any consenting adult would “go for” the idea of marrying a stranger and yet, I knew that most Indian marriages (and therefore a hefty percentage of the world’s marriages) were arranged.

After living in India for some time now, I’ve gained a much more comprehensive understanding of arranged marriages, including the arranging part, and why they both work and don’t work in modern Indian society. Instead of having the harsh view that I once had towards them, I don’t see arranged marriage as being entirely bad, so long as the son or daughter is open to it and parents take into consideration his or her best wishes.

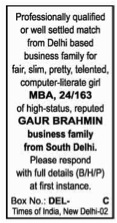

Of course, that’s a best-case scenario. The reality is that many parents have other concerns when it comes to marrying off their children. Most of the time, they are more concerned with how the potential mate looks on paper, how his or her family stacks up in terms of wealth, and the benefits of making the social alliance between families, which is usually between members of the same caste. Open any Indian newspaper and you’ll see entire pages devoted to “matrimonial classifieds,” most of which read something like this one, featured in India’s most reputable newspaper, The Times of India:

While it must be great to snag a match with a “fair complexion,” I don’t see that as any guarantee to happiness in life, which would be highest on my list of criteria when it comes to choosing my life partner.

Of course, many young Indians feel the same and opt instead to marry for love. Liberal-minded parents are on board with this, although they sometimes provide their own list of contingencies, especially when it comes to caste. The result is that many modern-day marriages in India are something of a hybrid between a “love marriage” and an “arranged marriage.”

I’ve spoken to quite a few people who are in this situation; however, it seems like falling in love is hard when there’s pressure from parents to marry early. One of my roommates, Neha, expressed this concern. At 27, she is well over the average age that women get married in India. But she is more than willing to get married, so long as it’s to someone that she at least has some feelings for. Although she has met some of the men that her parents have suggested for her, so far none of them have been promising. One potential candidate flew all the way from Mumbai to Jaipur to spend a day getting to know her, but when I spoke to her after the “date” she complained that, “He was so boring! I ended it early because we had nothing to talk about.”

When she moved in several months ago, she told me that she was from Jodhpur and her family still lived there. Since it’s fairly uncommon for non-married women to leave their families, I asked her why she had chosen to take a job in Jaipur. She replied, “Actually, I have chosen to go outside [of Jodhpur] to avoid pressure from my parents to marry. But still every day some member of my family is calling me, trying to persuade me to get married.”

Similarly, one of my male Indian friends is searching for jobs outside of India in order to deter his family from arranging a marriage for him at age 23. He says that he frequently has to fend off his parents when they try to pester him with proposals, including wallet-sized photos of his would-be brides.

Of course, sometimes the pressure is less overt. I’ve heard tales of passive-aggressive mothers who orchestrate meetings of potential matches by having candidates and their families “drop by” the house or office unannounced.

While I don’t personally know anyone who has married against their will, I know that it happens quite a lot. As a Westerner, I couldn’t comprehend how an educated, working adult could be forced into marriage. But one day my other roommate, Shruti and I were talking. She described a story she had read in the newspaper about a man who had been dating someone he loved and wanted to marry, but his parents didn’t approve. They chose a new bride and forced him to marry her, much to the outrage of his old girlfriend, who ended up turning on him with a gun.

I asked her, “But how could he let his family force him into marrying? Couldn’t he just refuse?”

That was when she laughed and tried to explain to me that Indian families don’t work that way, “You see, his entire family—grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, brothers, sisters—probably sat him down and told him that he had to marry. Since there is a great deal of respect between generations, he wouldn’t be able to refuse. They would keep him there until he agreed to do it.”

I asked, “But how could they force him do something that would clearly make him unhappy?”

“They care too much what other people think in society. They won’t let him marry the woman he loves and be happy because they worry what other people will say. Instead, they choose to ruin three lives by forcing a marriage that only they want. Now they must be feeling more shame after this incident than they ever would have had they just given him the choice to have a love marriage.”

It is true that the consequences of a forced marriage can be disastrous. Entire lifetimes can be wasted as a couple copes with anger and bitterness and there’s a greater risk of infidelity. But surprisingly, many arranged alliances actually work. From what I’ve observed, it’s because Indian people have a stronger sense of commitment.

India is a collectivist culture, where people are less concerned with “I” and more concerned with “we,” compared to the predominantly individualist culture in the west. The result is that marriage is an institution that takes into consideration the happiness of more than just one person; there are entire communities involved. With that said, it makes sense the divorce rate in India is one of the lowest in the world. People are less likely to pull the plug on the marriage when the going gets tough. This familiarity with the true meaning of commitment is something that is rarely seen in relationships in the West.

Of course, this approach is both good and bad. It’s not uncommon to hear news stories of women trapped in abusive marriages. And unfortunately, the parents responsible for the match are either too proud to admit they made a mistake or afraid of the social repercussions if they intervene in an unhealthy marriage.

But divorce is becoming less and less of a taboo in Indian society, and it comes down to the fact that marriage is changing as India absorbs the effects of globalization. Today, more people are living in big cities, couples are waiting to have kids and women are continuing to work even after they get married. The result is that marriage in India is slowly becoming more like marriage in the West, but not necessarily for the better.