“In Bolivia, one is chosen by divine selection,” explains Gregoria Calle, a native of Curahuara de Carangas—a rural town located about three hours south of the Bolivian capital of La Paz. As a young child, she was struck by lightning while crossing a river with her mother. Calle, dressed in a traditional knit cap and a full-length patterned dress, her hair in two long ponytails, remembers the incident that left her and her mother badly burned. “I knew then I was special and that my life had suddenly changed...I knew then I was a qollir [a traditional healer] and had the gift to heal.”

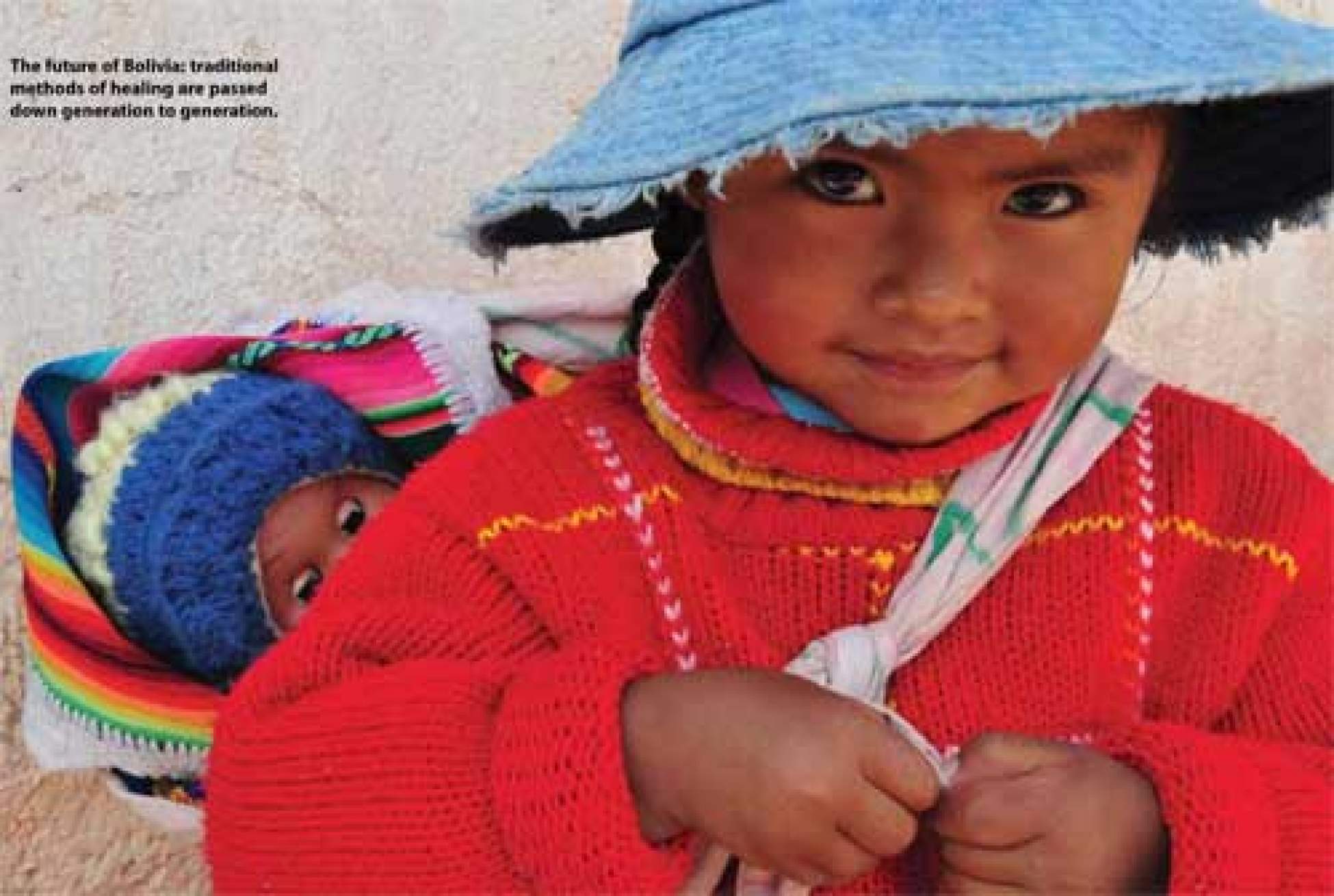

Now 35 years old, the midwife gently wraps a tiny newborn in an aguayo, a beautiful, handwoven Bolivian cloth. Mother and baby are united, and a sense of peace and tenderness fills the birthing room. Until recently, many women in Calle’s hometown declined to give birth at the local health centre in favour of a home birth assisted by a trusted midwife and healer like Calle. In the past, Calle’s clients would repay her with a donation of whatever they could afford. But now, because of a pilot project aiming to reduce the risks to women during childbirth, Calle has became the first midwife in Bolivia to be employed by the government and to work in public health.

Curahuara de Carangas is a municipality located in the Andes at an altitude of 4,000 metres. The community is small, with a population of just 5,000 people, and it is steeped in Bolivian tradition. Nearly all the residents here are indigenous, belonging to the Aymara ethnic group. The reasons why so many women don’t seek medical attention during pregnancy are not only geographic and financial, but also cultural. This is an issue that reaches across the country: it is estimated that about 90 percent of Bolivian women don’t go to a hospital or clinic to give birth.

It was this situation that Montreal-native, Miriam Rouleau-Perez came upon when she arrived in Curahuara de Carangas in July 2006, with her husband and two children in tow. A community organizer in public health back home in Canada, Rouleau-Perez went to Bolivia as a volunteer with Uniterra, an international volunteer programme created jointly by World University Service of Canada (WUSC) and the Centre for International Studies and Cooperation (CECI).

Rouleau-Perez initially travelled to Bolivia with the intention of working to combat infant mortality. Bolivia has one of the highest rates of infant mortality in the Americas, mainly due to diarrhea from contaminated water sources. When she arrived, Rouleau- Perez consulted with the doctor at the health centre and members of the community to see what their health concerns were. “We can say they have a high infant mortality rate, but how do they see it? What do they call it? What is their point of view about it?” she explains. According to the community’s doctor, the main health concern regarding infant mortality was women giving birth at home under dangerous conditions.

After speaking with the health centre staff, Rouleau-Perez decided to confer with a local midwife. At the time, Gregoria Calle couldn’t make ends meet solely as a midwife and healer and was moonlighting as municipal garbage worker. Rouleau-Perez stopped Calle on the street one day to ask for help with her own daughter who had been suffering from a cough. Rouleau-Perez took the opportunity to pick Calle’s brain and get her feedback on the issues surrounding home births. “She was the person who women would see to deliver their babies, and when everything was going well, her work was not recognized. But when there was a problem, her work was criticized [by the staff at the health centre]. They [midwives] just don’t have the support they need.... and they want that. They want to learn and improve their skills.”

Rouleau-Perez quickly discovered that there was a divide between practitioners of conventional medicine and practitioners of traditional medicine. So she got to work trying to bridge the gap, establishing a committee— including doctors, practitioners of traditional medicine, school officials and politicians— and encouraging them to hold regular joint meetings, in an effort to come up with a solution.

While Rouleau-Perez acknowledges that there were difficulties getting everyone to cooperate, the committee agreed that the need for action was dire. Ruth Bolaños, a Bolivian woman who now manages the project, explains, “Seventy-four percent of expecting women gave birth in their homes, with only their ill-equipped husbands attending to any complications.” This resulted in extremely high rates of infant mortality and infection. Bolaños has her horror stories from the field. An umbilical cord being cut with a piece of broken ceramic. A woman who gave birth surrounded by her llamas; “The placenta wouldn’t come out after the birth so she wrapped the umbilical cord around her big toe and pulled. These are the challenges we face in a place where clean water is often a luxury and hygiene is very poor.”

Perhaps out of the need to find a solution to the problem, the committee did just that: together, they applied to CECI for funding and began a pilot project whose name translates to “Aguayo for risk-free childbirth: Action for mothers and newborns.” The aguayo—the handwoven garment that the Andean use to carry babies, food and belongings— has tremendous symbolic meaning.

Through the pilot project, an intercultural birthing room was created. It is the first of its kind in Bolivia and features decor that imitates local homes so women feel more comfortable giving birth in an institutional setting. The rooms contrast sharply with the typical sterile hospital atmosphere: they are separate from the hospital, the walls are made of adobe and they are inviting and warm. They offer all the comforts of home, with kitchens and extra space for the family. Here, women can give birth with the help of a traditional midwife, in the position most comfortable for them. The birthing room was built next door to the health centre so that if complications arise, the doctor can be called; if a woman or child needs to be transported to the hospital, the ambulance is easily accessible. The importance of this cannot be underestimated in the Andes, where geographical complications can make travel slow and arduous.

With the help of the minister for traditional medicine, funding was secured for Calle to become an employee of the government and be paid a salary—enabling her to dedicate more of her time to her patients. A large part of the project’s success has hinged upon Calle herself, and her ability to convince women in the community to come to the centre when they went into labour and also for prenatal checkups. She already held the trust and confidence of the community and, according to Rouleau-Perez, that trust was instrumental in getting the kind of participation they needed to make the project a success.

Before the launch of the project in 2006, only about nine percent of women in the community would give birth at the health centre. By the end of December of the same year, more than 30 percent went to the health centre. And, by October 2007, at which point the project had been fully put in place with Calle on government salary, a remarkable 84 percent of women in the community gave birth in the health centre. But perhaps the most remarkable part of the project is that it enabled the community doctor and midwife to forge a relationship, ultimately providing better care for the women.

The project has not been without challenges, however. Any issues that arise must be solved through consultation with the local population, indigenous authorities, municipal government and hospital staff. Though midwives in Bolivia have gained more respect, a power struggle between the doctors and midwives remains. Some doctors are supportive, but others feel threatened that the Aguayo project hinders “progress.” And on the other side of the coin, Calle worries that some doctors may not fully understand what her patients want. “When the doctor arrives during a birth and takes over, I take a step back, and suddenly my patients lose their ability to choose their type of care,” explains Calle. Also, in rural Bolivia, the success of such a project depends on the forging of personal relationships. Since local doctors come from other areas of the country, and politicians can come and go, support for the project can be fragile.

But despite the challenges, the project has pushed ahead and progress has been made. Women are learning that they do have rights and this type of empowerment extends across generations of women in the communities. The mayor of Curahuara de Carangas, Romulo Lucio Along Huarachi, has nothing but praise for the project. He says, “The bottom line is that we are saving lives and women in Bolivia now have a choice. That is powerful.” The project showed such potential that in 2008 it received the Bill McWhinney Award of Excellence in International Development from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). Interestingly enough, the Bolivian government has issued a directive that health centres across the country should incorporate traditional medicine into their practices—an idea that this project is helping along.

Recently, other Canadian volunteers have travelled to Bolivia to continue where Rouleau-Perez left off. Sandra Demontigny, a 30-year-old midwife from Quebec, is now working to facilitate the expansion of the project to other municipalities. She also holds workshops for both midwives and mothers on pregnancy, labour and postpartum.

Demontigny and the team are excited about a new birthing room under construction in Belen de Andamarca, which will service a large indigenous community. Belen is located over 4,000 metres above sea level on a dramatic treeless landscape, about a six-hour drive from La Paz. People from other communities walk to the Belen health centre for care—a journey of up to six hours, sometimes in extreme conditions. One ambulance services the entire area.

“These remote communities have no communication, no phones, no internet, and things can get complex when emergencies arise,” explains Demontigny. “Planning precisely is part of the job in Bolivia, where supplies and resources can be absent. It’s always an adventure. You may know when you are arriving, but you don’t know when you are leaving.”

The team is also in the process of expanding the project to the municipalities of Corque, San Pedro de Totora and Santiago de Callapa. Ruth Bolaños heads the project. They’ve recently hired midwives in these communities, who are starting home visits with pregnant women to provide them with information on pregnancy and caring for newborns. Each community will have a birthing room that reflects that individual community, and women can give birth there or in the hospital. They can also choose whether they want to have a doctor or a midwife attend the birth.

And while the Canadian involvement was important to the success of the project, most of the ideas—and the hard work—came from within the communities themselves. Rouleau- Perez is adamant that she was only a facilitator, and the innovation came from within Curahuara de Carangas. According to her, her work was to mobilize the locals. She explains, “I always say, the forces were there, like when you put different pieces of a quilt and sew it together. The pieces were already there... I didn’t want to be a piece of it myself.”

Check out the photo gallery that features more of this project>>

Produced with the support of the Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency.