In Guatemala’s remote mountain villages, every man over the age of seven wears a sword, and every woman over the age of five, a plastic jug on her head. The sword, of course, is a machete; and the jug is a tinaja, a mixed Mayan and Spanish word whose origins are lost to prehistory.

When the metric system was invented in France during the eighteenth century Enlightenment, water was chosen as the defining element of the new rationality. Accordingly, a litre of water weighs precisely one kilogram; and the women of rural Guatemala will carry hundreds of perfect litres on their heads, every week, sometimes walking several kilometres to the nearest water-source and back. Such measurements in rural society are crucial to its survival, however approximate they may be in actual terms.

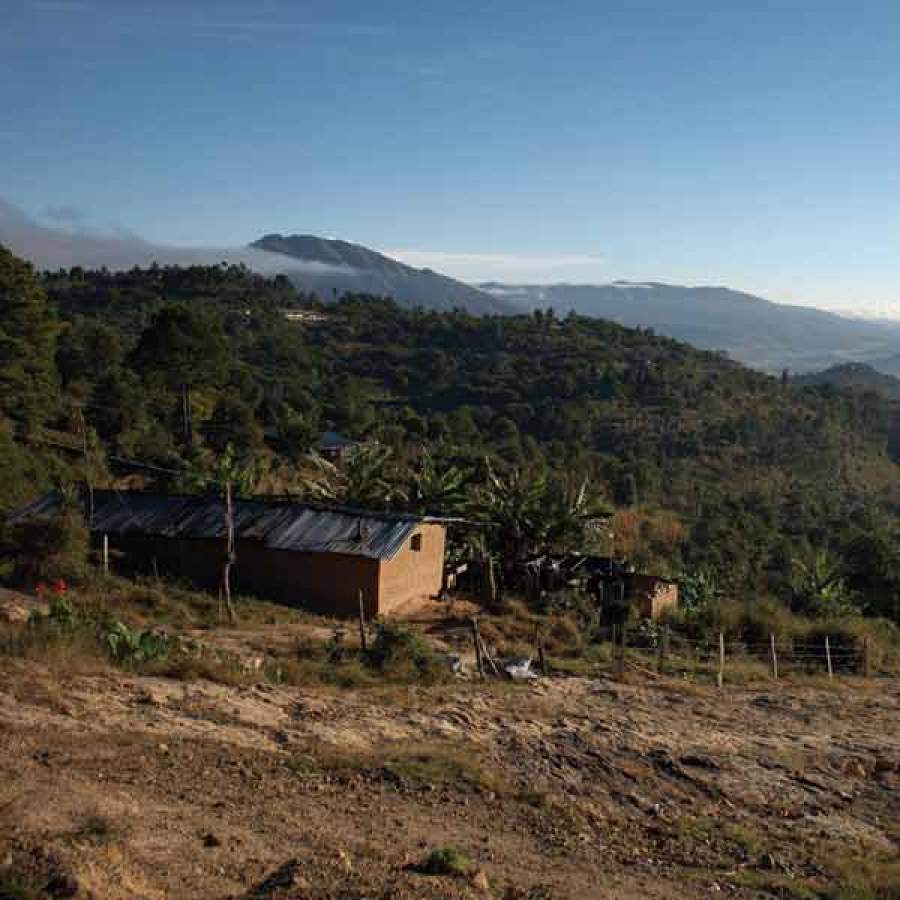

The finca, or family farm, of Laguna del Pito is located on the main road about 20 kilometres west of the Department Town of Jalapa—if the road is not blocked by falling rock, or washed out by the summer rains. The patriarch of this acreage is Don Margarito Jimenez, and he has divided his property among six sons and their large families. The site is 2 manzanas in size, or 60 acres, and it is abundantly watered after the recent rainy season. Don Jimenez and his clan are lucky. They share a large and deep pond, which appears to occupy about one-and-a-half acres at this date in late November. The pond means they do not have to depend on the tinaja, unlike most other families in their community.

At midday, while a constant stream of women and children bearing jugs file past Jimenez, he is happy to discuss his new crops with me.

“We use the cypress trees for shade for the coffee, and we also have maize, bananas, melocotón and durazno. Everything is good this year.”

The farm is lush to the point of excess. This year. But the country’s old system of reservoir ponds, cisterns and buckets puts whole communities at risk and prevents Guatemala’s economic progress at the national level. Essentially, the problem of water distribution and its containment is the problem of family economics, writ large.

In 2004, Ted Van Der Zalm, from St. Catharines, Ontario, became aware of these issues while volunteering in the area with a church organization. He mobilized a group of families around the Niagara Peninsula and founded Wells of Hope. One of their main goals, apart from building schools and bringing doctors, is to use the technology they have to drill deep wells in the highlands around Santa Maria Jalapa.

If they succeed, a lot of problems could be addressed. Ken Edwards, a manager for the organization, gives an example. “A few years ago a German NGO set up a coffee processing plant near Jalapa. Everything is still sitting there—drying sheds, roasters, pans and grinders. But with no dependable water source. It has sat unused for two years now—no water, no coffee plant.”

To put it another way—no proper water system, no economic growth beyond mere subsistence. This reality creates another one: a rural society based on having ten children per family, coupled with a 30% child mortality rate, and young girls having children at age 14. In this context, the farmers’ “biological insurance policy” of many children is as rational as the science of statistics, only more costly in terms of community life.

How far do you go to deliver support for a project?

Water-borne diseases, conjunctivitis, typhus, dysentery and the lot, are prevalent when farm animals share the same sources as humans. “There is clean water here everywhere. It is usually about 800 feet down," claims Lyse Edwards, project co-manager and Ken’s wife. It's not that simple, though. "After four years in the field, we are finding out that it is not enough just to dig a well.”

What the team must do is plug their project into the local infrastructure. Lyse offers up a hard-won refrain: “Wells need electricity for the pumps. Electricity needs permission, for power lines to cross properties. Permission needs… politics.”

The question, then, facing the Wells of Hope staff is simple: What is their mandate, exactly? How far do you go to deliver support for a project?

The weekly Saturday meeting of the farmers' association—properly called, with a typical Guatemalan love of elaborate titles, Asociación del desarrollo integral de perforación de pozos mecánicos de la comunidad indígena de Santa Maria Jalapa—takes place at 9 am sharp in Laguna Itzacoba, an indigenous village at 7,000 feet. They meet inside the former construction office where the Canadian team’s most recent well was drilled to 960 feet, and then capped.

Earlier this month, thieves stole over five kilometres of copper wire that the town had installed to bring electricity to this community. Without electricity the water can’t be pumped to the reservoir tanks. The cost to replace the stolen wire is $10,000, for two wooden bobbins of copper cable. This issue is the top concern of the association today.

Twenty-three communities are represented. The men arrive in white straw sombreros and freshly shined black boots; the two women representatives wear traditional indigo jupas.

These people have provided the labour for installing the electrical poles; they know that this single well can provide clean water for up to 10,000 people. But who is going to pay for the replacement wire?

There is talk of borrowing the money. Some non-members now want the poles off their properties; they don’t believe in the project any more. However, most farmers attending today are optimistic. They appear to relish the public meeting as a formal social event, and their public pronouncements are marked with proud assurance, even stagecraft. You can see it in their eyes: the electricity, and the water, will come. They have waited a hundred years since these things first came to the valleys below. Another year or two isn’t going to make a difference.

Back at Campo Esperanza, the Wells of Hope local office complex, Ken and Lyse Edwards are getting ready to host a team of new volunteers from the Niagara region. Surplus US Army tents and wooden platforms will house over 30 Canadian volunteers. They will command a 360-degree view of the green countryside, including a huge volcano that dominates the town, 20 kilometres away.

“Yes, earthquakes are a distinct possibility,” Ken admits. “And last night the power was out because of the thunderstorm.”

He points to the scorched microwave and refrigerator in the kitchen as more evidence of nature’s powerful intervention. Unaccountably, a large trailer that the organization was trucking through Mexico from Canada suddenly burst into flames. A third of the contents were lost before some passing Mexican farm workers doused the fire with water from barrels they were transporting. Earlier in the program, two drill rigs were lost hundreds of feet below the surface. The third rig was recently borrowed by a local man for his own efforts.

“We don’t know where our rig is now, or when it’s coming back,” says Lyse with resignation. “But we need a dual-rotor drill for this country. The ground is a mix of hard volcanic rock, and beds of gravel where the water lies. A proper machine costs a million dollars.”

The Edwards are filled with admiration for their team’s charismatic director, Ted Van Der Zalm. His energy is legendary. One day at the Campo, Ted looked across the Jalapa valley and saw that the white, Hollywood-style sign, “JALAPA,” emblazoned on the hillside had faded.

“He roused the kids, grabbed ten gallons of white paint and a sprayer, and headed up the mountainside,” Lyse recalls.” They painted all day in the hot sun until they ran out of paint. You see the bright spot at the tip of the J? That’s where they ran out of paint.”

Indeed, the tip of the 15-metre J is noticeably brighter, even from 20 kilometres away. The team is bursting with more such initiatives: concrete-block schools to be built, ladies’ sewing and cooking classes to be organized, used tools and schoolbags to be shipped from Canada in containers, new plants to be tested in the local volcanic soil. Ken Edwards takes an empty Gallo beer can and carefully cuts it in half.

“A starter pot for my broom flowers!” he announces, holding it high. The windowsills of the Campo building are now filled with many little pots. Edwards is especially fond of their latest concept, a plan to provide smokeless stoves to replace the traditional three-rock fire-pits used by villagers.

“Our design will use local pumice stone from the volcanoes for insulation. They will only cost two hundred dollars each. All we need is the money!” he says enthusiastically, as he cuts another beer can in half.

In the nearby town of Sanarate, a commercial sign from a local operator offers hope to water-deficient farmers:

Water Finder—I find water veins that can be dug by hand.

Finding water is a local obsession and it's been Ted Van Der Zalm’s second passion after teaching. The profound differences between the geologies of southern Ontario and Guatemala have created a steep learning curve for his team—as he freely admits, back in St. Catharines.

“You find water at 80 to 100 feet down in Niagara. There are aquifers running off the Escarpment and while our rivers are drying up, these aquifers are dependable. Guatemala is a technical challenge. The water is right under your feet, but a thousand feet down.”

Guatemala’s volcanic rock proved tough and unyielding, even at the level of inches.

"Wells need electricity for the pumps. Electricity needs permission for power lines to cross properties. Permission needs... politics."

“Last time I was drilling, I would spend 14 hours and accomplish four inches… four inches! The rig-drilling clamp would break and I’d lose thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment in a few seconds. I spend three-quarters of my time repairing equipment. We need better machines, to tap existing deep water-flows at 250 up to 650 gallons per minute.”

Theoretically, then, there is enough clean water under the volcanoes to utterly transform Guatemala’s rural life, but if Ted’s group is to put the plastic pot-makers out of business, such beautiful numbers need steady hands.

As Van der Zalm supervises a score of volunteers inside the Warehouse of Hope, a commercial greenhouse operation in St. Catharines, while they assemble the latest container-load of school supplies bound for Guatemala, he ruefully acknowledges their project’s predicament: “We are still looking for a miracle, but we are down to our last penny.”

At the finca of Don Margarito Jimenez, another long workday is over. The shadows of the black pine tress are lengthening over the green pasture around the pond. The white trumpet flower, whose pollen is said to be hallucinogenic, hangs sensuously over the cow path to the water’s edge. The farmer pulls a stick from the grass and thrusts it deep into the crude stone cistern dug into the shore, searching for the depth of the water. He pulls it out, places the wet stick beside himself, and breaks into a wide smile. The stored water is taller than his head; the family is secure now that the rainy season has ended. Behind him, a young woman stands waist-deep in the middle of the pond, pouring water from a bucket over her glistening hair.

The glowing light has transformed their long day of work into a full communion with nature, and everything lapses into a perfect stillness.

Read more about the role of gender in regards to collecting water.

Learn about the Canadian-made drill used to locate potable water across the world.