In a small, worker-run cooperative in an impoverished Argentinean neighbourhood, the workers of an after-school daycare programme argue for three hours. They yell, scream and cry... over who gets the privilege of safeguarding the keys to the all-important supply closet. Workers battle it out over personal rivalries and the tiniest administrative decisions until finally an agreement is reached.

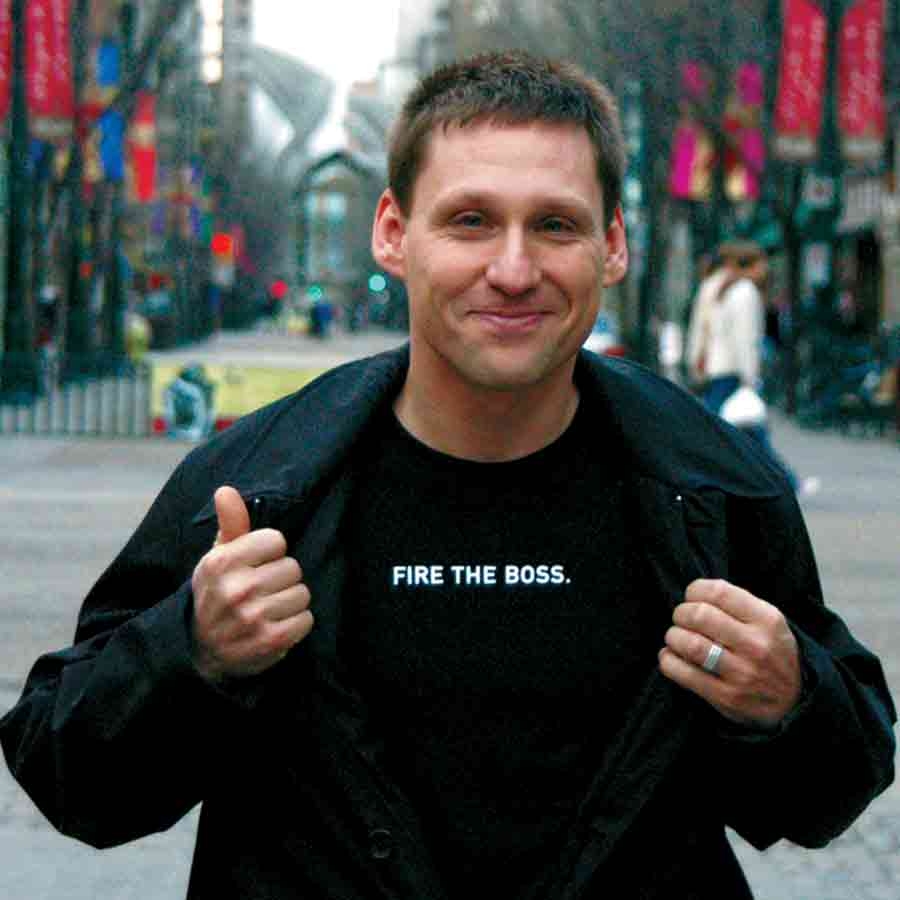

Seem petty to you? Not so, says Canadian television journalist Avi Lewis, who witnessed this meeting among others when he spent several months in Argentina shooting footage for his acclaimed 2004 documentary, The Take.

In fact, it is all part of 'economic democracy'—giving workers an element of control in their workplace and the way they do business. It is a concept that Lewis believes in strongly, and one that he is now actively encouraging with an organization that he co-founded following his documentary.

Some of you may know Avi Lewis as the candid host of CBC Newsworld’s The Big Picture. Others may know him as the youngest public face of the Lewis family—a prominent Canadian family with a record of political activism that dates back to the early 1900s—and son of Stephen Lewis, former UN special envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa. So it may seem ironic that Avi Lewis, a veteran of Canadian political activism himself, had to travel south all the way to Argentina—a country recovering from political and economic crisis—to see real democracy in action.

Indeed, Lewis says democracy is exactly what played out in that Argentinean cooperative, where a small administrative decision turned into a row over personal dynamics. And even though Lewis laughs when he recounts the story, it’s clear that this kind of meeting—where everyone gets a voice—makes sense to him on a number of levels.

“There are tears and there are yells,” says Lewis, “but at the end of it they come out of it as a group that’s been honest and they work so much better together. That is something that I really learned. Real democracy in action will always surprise you. It will always be harder than you think and it will always be more worth it than you can ever imagine.”

Lewis’s film, The Take, documents what has been dubbed the recovered factory movement in Argentina. Workers have taken over abandoned factories in the wake of the country’s 2001 economic collapse, and then restarted them using a totally new egalitarian system without bosses, owners and hierarchies. The model of the recovered factory featured in Lewis’s film—including the values of cooperation and equality in the workplace—is beginning to gain momentum in other parts of the world. But the reason the film resonates with people so deeply is simple: it carries a powerful message that no matter how bad things seem, change can be achieved and the apparently powerless can take control of their lives.

Lewis and his wife, writer Naomi Klein, were looking for something specific when they travelled to Argentina in 2002 to research the film. Klein had just finished her book, No Logo, and was touring around the world; Lewis was hosting a daily talk show at the time. Both were—and still are—heavily involved in the debate about globalization and the problems that are often associated with it, like worker exploitation, inequalities, environmental damage and human rights abuses. But the daily struggle was starting to put a strain on the couple, and they made a conscious decision to look for an alternative.

“We were arguing with the bad guys every day and every night, fighting this fight around globalization, and we were really burnt out on protesting and critiquing,” explains Lewis. “We were just angry all the time. We said to ourselves, we need to find something that we support, we need to find something that is a solution, we need to find something that really inspires us—and we need to tell that story.”

The couple travelled to South Africa and Brazil before settling on Argentina. They were looking for a place where people were developing sustainable local economies—economies that decrease inequality, share natural wealth, and don’t destroy the environment. And they knew they found what they were looking for when they visited Argentina in the wake of the country’s economic crisis.

“There were literally explosions of local democracy and economic alternatives everywhere you looked in Argentina at that time,” explains Lewis. “So when we saw that, we thought OK, there is enough going on in this one country that we could make ten films right here. So we went home and got the financing together for the film—that took almost a year. And when we got back to Argentina, there were 200 recovered companies, 198 of which had been occupied since we left a year earlier, so it was pretty clear that there was this phenomenon that we wanted to focus on.”

The Take aired at Toronto’s HotDocs festival in 2004, and had three sold out screenings at the Bloor cinema. But as Lewis recounts, after the initial rush, when the pair went home, “It had been three years of work and the phone didn’t ring and there were no distributors calling. It took me a couple of months to realize that to get anyone to see the film, in order to secure commercial distribution of the film globally, it was going to be a whole new campaign. Then I spent the next year of my life going to film festivals, sucking up to distributors and pitching and tap-dancing my ass off trying to get people to take the film and distribute it.”

"We were really burnt out on protesting. We said to ourselves, we need to find something that is a solution, something that really inspires us, and we need to tell that story."

Lewis had no intention of using The Take to launch a formal NGO, until a chance encounter at a screening in New York City. After the show and a brief question and answer period, a young American who introduced himself as Brendan Martin approached Lewis in the hallway of the theatre. Martin was excited and enthusiastic, almost vehement that he had an idea of what could be done concretely to help the workers in Argentina. Lewis, at the time, had no idea that this encounter would lead to a lasting friendship and work partnership. “To be honest I thought he was a little bit over the top,” Lewis says jokingly. “I had no idea that he’d been thinking about this for like ten years of his life and all of a sudden he had found the place where he could put into action ideas he’d been working on for years. I just thought he was a New Yorker who was standing a little too close.”

After a brief conversation, the two exchanged email addresses. A couple of weeks later, Lewis received a detailed proposal from Martin to start an organization—and that, according to Lewis, is when he started to take Martin seriously.

In November 2004, the pair officially launched The Working World, with initial funding from their own pockets and private donations. Martin moved to Argentina to handle the daily operations and Lewis handled the communications and publicity. But Lewis admits that Martin came up with the original plan of action—one that he would have never thought of himself. “I tend to organize politically,” says Lewis, “to do political advocacy and media work, and petitions and political pressure and stuff like that. Whereas he [Martin] looked at the situation in the film and said ‘Jesus Christ, these guys have no capital!’

The Working World supports the Argentinean recovered factory movement by giving small-scale loans to the workers. In post-crisis Argentina, where there was virtually no credit, no financing and no government support, capital was what the newly recovered factories needed most in order to buy raw materials. But even though the cooperatives needed financing, they were apprehensive about accepting support from The Working World, according to Martin. Initially, they had to approach cooperatives and offer funding; they also had to prove to them that they were open and honest. Now, they have built enough of a reputation that cooperatives approach them for funding.

Soon after Lewis and Martin first started working together, they realized that their methods were very different. When Martin did the first mock up of the website, he wanted to put the organization’s accounts online—the companies they were working with, their schedule of loan repayments, the interest that was made on the money they had in the bank, and their office expenses. “He was just proposing to put them [our books] on the website!” says Lewis. “And I was like, you’re nuts!”

But this was part of Martin’s larger theory of doing business openly and honestly—and being 100 percent transparent about it. Lewis was apprehensive at first, but he recalls, “He [Martin] said no. This is the principle—the principle is transparency.” So, the accounts went online, and have remained there since.

"You don't have freedom of expression in your workplace. Try telling your boss exactly what you think of her."

Lewis explains Martin's reasoning. “The problem with the global consumption system is that when you pay 100 bucks for a pair of sneakers you assume that the worker is getting a tiny minority [of the money], but where does it actually go? How can we ask people to embrace a democratic economy if we’re not prepared to live it?”

In their first year and a half of operation, The Working World gave out 13 loans to various cooperatives. In their second year, they gave out another 22 loans—and a little money goes a long way in Argentina. Two loans totaling a little over $11,000 Canadian helped a shoe-making cooperative in a shantytown outside of Buenos Aires build a completely new factory. And, according to Martin, this example is their biggest success story.

“They were crammed in the back of a house of a cooperative member—and this was slowing them down, they couldn’t add workers. But the product was excellent, like a multinational shoe and they churned out 1000 every month.” Since receiving loans from The Working World, the shoe factory—called Desde el Pie (meaning ‘from the foot’)—is expanding, and looking for new workers. Salaries have skyrocketed from an unstable 600 pesos ($226 CDN) to a stable 1200 pesos ($452 CDN).” In that neighborhood, according Martin, those results are tremendous.

The Working World tries not to turn anyone away. If they are approached with an idea that seems too large or unfeasible, they might suggest restructuring the idea instead of turning it down flat. “We’re kind of softies,” admits Martin. “We really want to work with anyone who could use our help. But obviously we need to be careful because we’re loaning money. If we can’t get it back, we’re not going to function.”

Both Lewis and Martin strongly believe in economic democracy—a complicated sounding term that really just means making the workplace a democracy. It’s about people having an element of control, or a say, in the way their workplace is run and the way they do business. “The idea that we say we live in a democracy but we spend at least 40 hours a week—many people 60 or 80 hours a week, [...] the majority of our waking lives—in a place where we don’t have fundamental human rights,” says Lewis.

“You don’t have freedom of expression in your workplace,” he continues. “Try telling your boss exactly what you think of her. You don’t have freedom of association in your workplace. You can’t just get together with 25 of your fellow workers at any time of the day in the workplace and discuss everything that’s screwed up about it. And you certainly don’t have equality rights in the workplace, because you see people with less talent and better ass-kissing skills making more money than you do.”

But Lewis says that democratic workplaces are not only fair and just—they are also economically profitable. According to him, if people have some power over workplace decisions they will have more invested in the quality of their work and the company itself. “We kind of forget that the people who do the work are the ones who really know what they’re doing,” says Lewis. “They’re really the best people to organize the work so that it gets done in the most efficient and fairest and least stressful and difficult way. These workers in Argentina, who worked very happily under bosses for 30 years, didn’t really find out what they were capable of until their bosses screwed off and took all the raw materials and as much of the machinery as they could get out, and just abandoned the factory. Then these workers had to do it themselves.”

And the recovered factory movement has started to spread. Venezuela held the first annual pan-Latin American meeting of recovered factories with representatives from countries like Bolivia, Brazil, Uruguay, Venezuela and Argentina. The Working World has even had contact with factories in Siberia and Iraq. And according to Martin, it wouldn’t have been on the radar if it weren’t for Argentina. “They looked to The Take as a model,” says Martin. “The inspiration to workers has been huge… they are inspired by the concept that they really can have control over their own lives.”

While The Take has been held up as a model to workers around the world, Martin thinks that it has the power to speak to young people on another level as well. Young people can use this movement as an inspiration—not just an inspiration to take over factories, but to take action against injustice generally. “A lot of young people aren’t happy with the system but are not sure what the alternatives are, what else we can do,” explains Martin. “When your factory closes and you think there is nothing you can do—well there is. Or even with your system generally. The reason Avi made the movie is to say that if you see a problem with your system, there is something you can do, don’t just take it lying down.”

Now, two and a half years since The Working Word has been in operation, Lewis continues to work closely with Martin. Lewis officially handles the public relations and communications; but in reality, he participates in all sorts of decision making—big and small—like how to guide the organization, devising strategies and implementing them. He continually takes on new projects, like hosting the second series of CBC Newsworld’s The Big Picture, which is set to air in the spring. But the thread that holds it all together for Lewis is his continued activism and political drive—his filmmaking, public speaking and journalism all stem from the same desire to make a difference. He says his political drive is what gets him up in the morning, and it’s what gets him yelling at his newspaper. And Lewis no longer differentiates between his work week and his weekends; for him, it’s all work that he loves to do. “When you get to work with things that you basically love and support,” Lewis says excitedly, “then the barriers between work and life just completely break down.”

Lewis, now almost 40 years old, acknowledges that he still needs to take time off occasionally—to take care of himself and to make sure he keeps his motivation up. “Burn[out] is absolutely part of having an activist life, there’s no way around it,” Lewis explains. “You have to devise strategies as you get older to take care of yourself, to take care of the people around you—to make sure to get some sleep, to get away from your computer and get some air, to get on your bike and ride, to actually have fun, and not dwell exclusively on horror and injustice. But all of those are strategies to give you more energy for doing the work that’s so important to do.”

And while Lewis admits he gets discouraged when he doesn’t see results, he tries not to let it interfere with the bigger picture. He questions himself at least ten times a day, but always manages to keep working—and to keep fighting. “I don’t think there is anything more frustrating or dispiriting than trying to change the world,” says Lewis in a matter-of-fact tone. “But I think that the truly dispiriting thing is knowing that you’re not doing anything—and that’s what I couldn’t live with.”